The decent ones left the Communist Party after August 1968

Download image

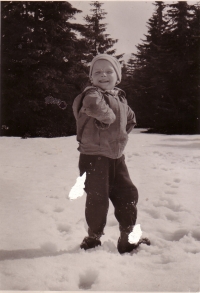

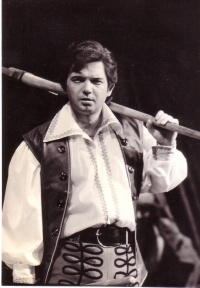

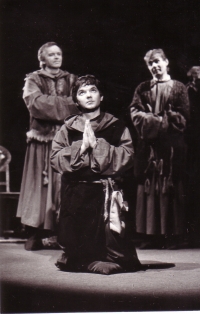

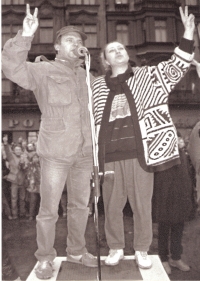

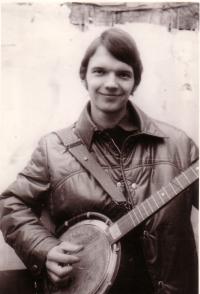

Přemysl Kubišta was born on 12 December 1955 in Prague. His father, Přemysl Kubišta, was a researcher of machine tools and machining, his mother a designer. His father was active in the anti-Nazi resistance during the war and was a member of the Communist Party until 1968, while his mother came from a family that was deprived of its business in wholesales and their livelihood by the communists after February 1948. Přemysl showed singing and acting talent from childhood, which he inherited from his maternal grandmother. At the age of nine he got his first lead singing role in a television adaptation of the opera Kominíček. In August 1968, at the age of thirteen, he witnessed the killing of a girl by the occupying troops at the Czechoslovak Radio building. After graduating from primary school, he did not get into the acting conservatory, and did not try music because of his voice modulating during puberty. He trained as a locksmith. In 1974, he joined the Army Art Ensemble as a singer, where he served his basic military service. In 1978–1985, he studied at the Conservatory of Music in Prague, majoring in opera singing. Then he was engaged in the National Theatre in Brno and since 1987 in the operetta DJKT in Plzeň. In November 1989, he was one of the first activists who informed and incited the citizens of Plzeň to demonstrations and strikes. In 1999, he left the Plzeň theatre and, with his colleague Pavel Kikinčuk, founded the Pluto Comedy Theatre. He considers his role of his career to be the character of Josef Švejk in the film Toulavé house (Wandering Little Geese)