I was no hero

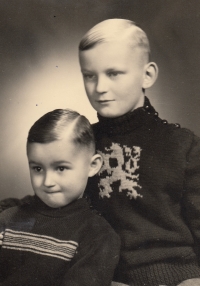

Ladislav Kukla was born on 15 January 1943 in Prague to Jaroslav and Ladislav Kukla. He spent the first years of his life with his mother and older brother in Jirny near Prague. In 1940, his father refused to renounce his Czech nationality, so he was sent as a doctor to the Reich. Before the liberation, his father escaped from the deployment and returned to Prague, where he took part in the fighting on the barricades during the uprising. After the Communist takeover, his father refused to join the Communist Party and his practice and property were nationalized. In 1959 he was arrested and sentenced to three years imprisonment. He was released in 1962. Ladislav Kukla graduated from the Secondary General Education School (SVVŠ) in 1960. He was not allowed to continue his studies and worked as a labourer. In 1969 he was accepted into the Union of Czechoslovak Visual Artists (SČSVU) - painting. He had exhibitions in Brno, Prague, but also in many other places abroad - for example in Germany, Spain and even in New York in 1972. In 1974 he was expelled from the SČSVU. In 1975 he received a painting scholarship at the Royal Swedish Academy of Arts, in response to which the regime banned him from exhibiting and issued a travel ban. Due to the pressure of the regime, he had serious psychological problems. In the end, his faith helped him. In 1993 he started teaching at the Secondary School of Graphic Arts and later at the Higher Vocational School of Graphic Arts in Jihlava. He has exhibited both at home and abroad. He was rehabilitated and his membership in the Union of Visual Artists of the Czech Republic was renewed. He was a member of the International Association of Art - UNESCO. Since 1991 he was also a member of the Society of Visual Artists of Vysočina. In 2024 he lived in Jihlava.