Without God’s blessing, human effort is futile

Download image

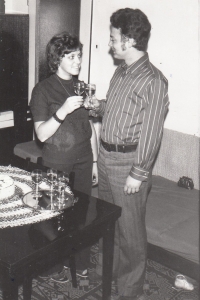

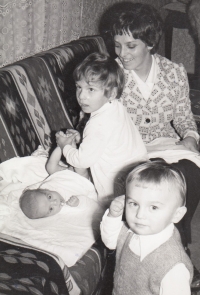

Stanislava Kulová (nee Bodláková) was born on 18 October 1951 in Svratka, Vysočina, into a deeply religious family. Her father, František Bodlák, joined the resistance immediately after February 1948 and used a borrowed motorbike to distribute Pastoral’s Letters in the surrounding parishes. Priests released from communist prisons found refuge with the Bodláks during the one-party rule. Mother Anežka Bodláková washed and cleaned their laundry, picked up their lice, cooked for them and hid their correspondence. At the age of two and a half, Stanislava suffered from severe cerebral palsy - because of her disability and walking on crutches, she was often the target of ridicule by her classmates. Because she had a bad report card and, as a girl from a Catholic family, a cadre profile, she enrolled at the Higher School of Economics in Trutnov - at the other end of the country, thinking that separation from her parents would remove her from their influence. Instead, in Jánské Lázně, where she lived in a dormitory, Stanislava met a political prisoner, Antonia, called Tonička, Hofmanová, with whom she struck up a lifelong friendship. During her adolescence, she then joined the Fokolarin group, which at that time included, for example, František Radkovský and Miloslav Vlk. In the first half of the 1970s, the Brno apartment of Stanislava Kulová and her husband Zdeněk became a centre for secret religious meetings, where lectures and masses were held. After her divorce in 1975, Stanislava was left alone with her two children and earned extra money by transcribing samizdat. In 1989, she signed and disseminated Several Sentences and a petition for religious freedom by the activist Augustin Navrátil. Throughout her life she worked as an accountant and, in the period after the Velvet Revolution, as a churchwarden at the Church of St. Mary Magdalene in Brno. She raised two children, Stanislava and Jiří. At the time of the interview, Stanislava Kulová lived in Rajhrad.