I’m going to lose my family and my country, but I can’t help it.

Download image

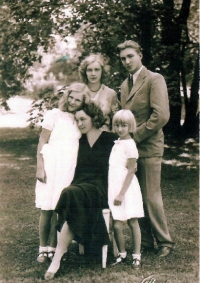

Vlasta Lavalová, née Čepková, was born on 9 December 1924 in Pilsen, the youngest of four children of Frida and Vlastislav Čepek. Her father, a graduated engineer, was a building executive and her mother, active member of the Sokol movement, came from the prominent business family of Macenauer. Vlasta’s world view was also influenced by distinctly patriotic atmosphere in the family. Before the war, the family had been in contact with a number of important personalities. Vlasta’s older sister Emma Čepková is still considered to be one of the best Czechoslovak tennis players. Her husband was Eduard Outrata, a member of the exiled Beneš government during the World War II and a prisoner of the communist regime in the 1950s. The Macenauers owned a large farm and castles in Úlice and Pňovany, villages located west of Pilsen. Vlasta spent her childhood and adolescence in both castles, and also a period when she was forced to work for the Great German Reich. Úlice and Pňovany became part of the so-called Sudetenland, the family’s property was confiscated, and they were forced to move out. Only Vlasta’s uncle, Pavel Macenauer, remained at the castle in Úlice, as a temporary administrator tolerated by the Germans. Due to the situation in Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia, Vlasta was unable to complete her grammar school studies and was to leave for Germany for forced labour. At the same time, she became seriously ill and her mother and uncle managed to negotiate for her to be assigned to work in the castle garden in Úlice. During the years 1938-1945 she began to keep diaries in which, through the eyes of a teenage and sensitive girl, she described the gradual change in relations between Czechs and Germans and events in the borderlands during the war. The diaries were published in a book under the title No Executions Reported Today. In 1942 she met a French prisoner of war, Luis Laval, in Úlice. The fragile relationship, complicated at first by external circumstances, eventually grew into a lifelong partnership. After the war, Luis and Vlasta got married and left for France, returning to Czechoslovakia two years later. In France, full of hope for a better future, they joined the Communist Party, and both succumbed to the illusion of a fairer world under communist leadership. Vlasta became involved in “building of socialism” and volunteered to work manually in the construction industry. At that time, she also considered it fair that the Macenauer family property had been completely subject to nationalization. She was losing her illusions gradually, most of the members of her extended family were discriminated after the communist coup, and the castles of Pňovany and Úlice gradually turned into ruins. Vlasta and Luis remained permanently in Czechoslovakia, although the occupation in August 1968 became their greatest disappointment. After five years in construction, Vlasta returned to working with flowers and Luis worked at Armabeton until his retirement. Together they raised two sons. Vlasta Lavalová passed away on 22 October 2021.