Whenever we were clueless we left it up to the Hucul Pony

Download image

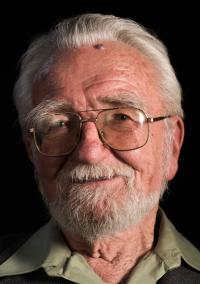

Otakar Leiský was born on 11 November 1925 in Pardubice. As a five-year-old he moved with his parents to the Slovak town on Prešov where following the economic depression his father found a job in construction. Shortly after the outbreak of WW II the Leiský family moved to Prague where Otakar joined the anti-Nazi resistance group Zpravodajská brigáda which had shared information on the movement of German armies with the authorities in London. After the war he began studying medical school but after five semesters left it and transferred to natural science. Following a military service with the artillery unit in Brdy he was admitted to the Ministry of Education, Department of Environmental Protection, where he helped establish this new field. In 1958 he in cooperation with the National Museum founded the Association for Environmental Protection (TIS) which had in 1969 gained the status of an independent organization, and which operates to this day. In 1972 TIS responded to the immediate risk of extinction of Hucul Ponies and by establishing the Hucul Club, and managed to save the breed. Otakar Leiský remains an active environmentalist and lives in Prague.