Life goes on and you’ve got to be grateful for what you have

Download image

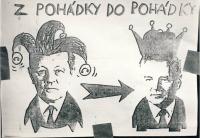

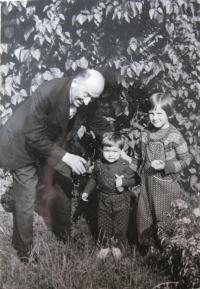

Ludmila Levá, neé Limpouchová, was born in Pilsen in 1934. She comes from a large Catholic family. Her uncle, Mons. Josef Limpouch (1895-1965) was an important clergyman in Pilsen, an active member of the Czechoslovak People’s Party and of the sporting organisation, Orel (the Czech word for eagle). He joined the resistance movement during WWII and from August 1944 till the end of the war, he was imprisoned in a Nazi jail. After the liberation he participated in public activities again. In 1945-1946 he even became a deputy of the National Assembly. In 1951 he was arrested by the Communists and held in prison until 1960. After a year and a half of detention he was sentenced to ten years of imprisonment by the County Court in Pilsen in September 1953. He was sentenced for the crime of high treason, supposedly as a traitor and agent of the Vatican. He was imprisoned mainly in the Valdice and Leopoldov prisons. In 1960 he was granted amnesty and was finally released. He didn’t live long enough to experience his rehabilitation in 1990. Persecution also affected other family members. Mrs Levá’s sisters, Marie and Terezie Limpouchová, were moved from their flat in Pilsen to a dilapidated parish house in Potvorov. Ludmila Levá studied at a grammar school and graduated from Social Nursing School in 1952. After graduation she worked as a nurse, first in the surgery department at the Škoda factory hospital. There she treated people who were injured during the Pilsen uprising in 1953. Later on she was employed at the Consultative Department in Doubravka Health Centre and at the Consultative and Social Department of University Hospital in Pilsen. She retired in 1992.