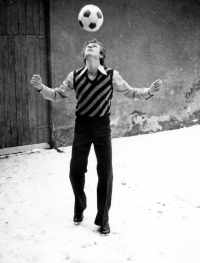

How a pig herder won the Olympics and scored goals against the Bayern

Download image

Verner Lička was born on 15 September 1954 in Hlučín in the area called Prajzsko where mostly Germans lived. His father Paul Litzka and mother Lydie Kaštanská were of German nationality, so his father had to enlist in the Wehrmacht during World War II. He was not yet twenty years old. Verner Lička’s maternal uncles also fought in the army of Nazi Germany. One of them did not return from Soviet captivity until eight years after the war; the Czechoslovak authorities refused to let him into his former homeland and he went to Wuppertal, West Germany, where his wife and three children followed him. In 1955 Paul Litzka changed his name to Pavel Lička. Verner Lička grew up with his sister Jana who was two years older. He used to visit relatives with his mother in Wuppertal where he used to spend his holidays before the occupation of Czechoslovakia in the summer of 1968. Their German relatives persuaded them not to return to Hlučín because they expected the occupation of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact troops. However, the family decided not to take up the offer to move to West Germany. Verner Lička started playing football at age 11 in Hlučín, then added basketball and played as a point guard in the youth league. At the age of 17 he played for the adult A team in Hlučín, then moved to Dolní Benešov and Opava, where he met his coach Evžen Hadamczik. In 1973 he enlisted in the army to play with Dukla Tachov where he played on the division level two years and was allowed to train in two phases in the morning and afternoon. In the summer of 1975, he returned to Opava, and in January 1976, he transferred to the first league team of Baník Ostrava. With Baník he won two championship titles and reached the semi-finals of the European Cup Winners’ Cup. He became the top scorer in the Czechoslovak league twice, scoring 103 goals in the top Czechoslovak competition. He made nine appearances for the national team, scoring once. He played for the Czechoslovak Olympic team, and in the 1980 Moscow Olympics qualification he contributed to the advancement over Bulgaria, Poland and Hungary. He scored four goals. At the Olympics, he added another goal in a 2-0 win over Yugoslavia in the semi-finals. He was also in the line-up that beat the German Democratic Republic 1-0 in the final. Before the Olympics, he helped Czechoslovakia win third place at the European Championships in Italy. A skiing injury kept him out of the 1982 World Championships. In 1986 he went on a foreign assignment to Grenoble, France, and after a year moved to Belgium, where he experienced the Velvet Revolution of 1989 with his wife and two sons. He returned home for family reasons in 1992, and in 1993 he became an assistant coach to Václav Ježek for the Czechoslovak national team. With the Czech national team, he witnessed winning silver medals at the 1996 European Championships as the assistant coach to Dušan Uhrin Sr. As the head coach, he worked with the Czech national team, coached Baník Ostrava at club level and made a name for himself in Poland. He coached Polonia Warsaw and won the Polish championship title with Visla Krakow. In 2022, he lived in Ostrava-Hošťálkovice and educated football coaches at seminars.