I was born in a slightly complicated situation…

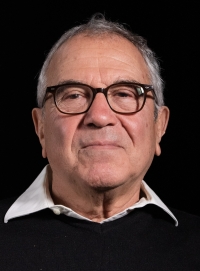

Gérard London was born on April 3, 1943 in a Paris prison in a special women’s ward, where his mother was imprisoned by the Gestapo and the French police for the resistance to the occupation of France. Gérard spent the first fourteen months of his life in prison with his mother. After being deported to the Ravensbrück concentration camp, he was left alone for several weeks there, until his grandmother, his mother’s mother, came for him. He had a sister who was four years older, who was born in Paris, and a brother who was seven years younger and born in Prague. The political activity of both parents had serious consequences for the whole family and significantly affected Gérard’s childhood and adolescence. His parents were imprisoned in concentration camps during the Second World War, and his father was sentenced to life imprisonment in a trial with R. Slánský in the 1950s. The family faced persecution; Gérard was the object of a constant ridicule from his classmates. He completed the first four years of schooling in Prague, the next four years in Paris, then the eighth grade again in Prague. After graduating from the eleven grades school (today’s secondary grammar school), he started studying medicine. It is clear that all the life turbulence and hardships to which he was exposed in childhood are stored in his memories, but they also prepared him for the life in adulthood. When he talks about complications or problems, he always adds a word slightly. He graduated from two medical faculties (in Prague and Paris), where he completed his studies together with postgraduate studies in 1970. He thus stood on the threshold of his future career as a renowned nephrologist. He has received significant awards for his scientific achievements. Since 1966, he has been permanently based in Paris, where he lives with his wife, two sons and grandchildren.