If you say to somebody today that you were transmitting messages to London, they won’t be able to imagine what it all involved

Download image

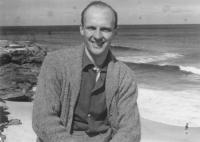

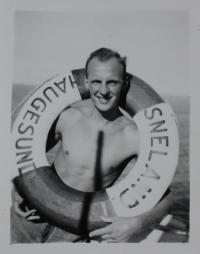

Jan Lorenz was born October 13th 1924 in Prague. He grew up in the Smíchov neighbourhood and attended an elementary school in Malá Strana. He also attended the Sokol sports club in Malá Strana, and he participated in the Sokol national meetings in 1932 and 1938. The majority of his friends, however, came from a water-scouts´ club, of which he was also a devoted member and with which he was going on trips, descending Czech rivers. His co-workers in the resistance movement in the Intelligence brigade were then also mostly former scout members. He organized transmission of reports from his friends, which he would then hand over to his messenger. In May 1945 Jan Lorenz took part in the Prague Uprising, but he was not involved in direct combat. In 1945 he began studying at the Faculty of Architecture of the Czech Technical University, but was dismissed for political reasons in 1949. In January 1950 in the Domažlice region; he and his friend from boy scouts crossed the border over to Bavaria. In Germany he arranged his emigration to Australia, and in December 1950 he then sailed to Sydney. In 1955 he resettled to San Francisco in the United States. He worked a technical engineer; living in California and Kentucky. After 1990 he returned to Czechoslovakia, and now lives in Prague in the Malvazinky neighbourhood.