I do not regret anything

Download image

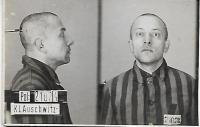

Milada Machů was born as Milada Holbová on 7th January 1934 at Bylnice near Valašské Klobouky. Her father was a miller, a hard working man respected by the local community. As an active member of the Sokol Movement, he was imprisoned for two years during WWII. Although he returned home from Auschwitz with his health totally devastated, very soon he took part in the activities of the Alfa (Rada tří organization) anti-Nazi resistance group. The witness also secretly helped in the resistance movement - she distributed messages and leaflets. After the February 1948 Communist coup, her father was arrested, imprisoned and released after two years without a trial. The witness could become a teacher only with difficulties. She completed her distance studies for upper primary level and all her active professional life worked as a teacher at the Basic School at Újezd.