A man whose life creed does not contain anything for which he would be willing to sacrifice his life can only live a life that is dull and uninteresting

Download image

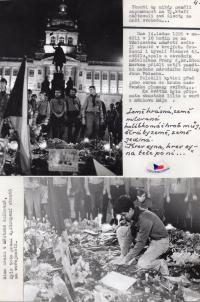

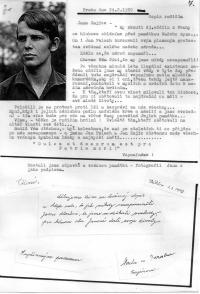

Petr Maišaidr was born November 15, 1940 in Prague. His father came from Nové Město pod Smrkem from a mixed Czech-German family, he was drafted to the wehrmacht and after the war remained in Munich and worked for the Americans - Petr thus never knew him. He was brought up by his mother and grandmother. He studied for eleven years at a school in Prague-Vysočany, after his dismissal he eventually graduated in Litvínov. His love for nature and camping became fully manifested there, and as a seventeen-year-old he obtained a log-cabin in Český Jiřetín. After his military service he returned to Prague and worked in the Léčiva company. In 1968 he joined the scouting movement and became a member of the Club of Committed Non-Party Members. During the events of August 1968 he was involved in street clashes and in the defence of the Czech Radio building. After the Soviet occupation and the ban on scouting in 1970 he carried on with scouting activities illegally. He is a Charter 77 signatory. Apart from scouting he was also active in the Czech Union for Nature Conservation throughout the 1980s. From 1995 he was working in the Office for the Documentation and Investigation of the Crimes of Communism, and in the early 1990s he founded a scouting centre Atahokan, which was later renamed to the Brother Mašín Centre.