When the uprising broke out, guns were handed out

Download image

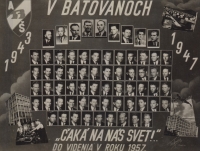

Karol Marko was born on 26 May 1929 in Dolni Lopasov in the Piešt’any district. He was the fifth of nine siblings. His parents, Ľudovít and Amália, were peasants, farming six hectares of arable land, which they had to surrender after the February coup and join a cooperative. From the age of 11, Karol Marko grew up with his aunt in Veľké Šenkvice. After graduating from the local primary school, he entered the Bata boarding labour school in Batovany (today’s Partizánske). The Slovak National Uprising caught up with him there. After 1948 he joined the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, where he remained until the Velvet Revolution. As a graduate of the labour school, he worked in Bat’a’s factories in Batovany - later the “August 29th Factory” in Partizánske. He remained there until his retirement in 1989. During his work engagement he also worked as an official of the ROH factory club, thanks to which he visited a number of Eastern Bloc countries. At the time of the interview (2020) he lived in Partizánske.