All the bad serves someting good in your life

Download image

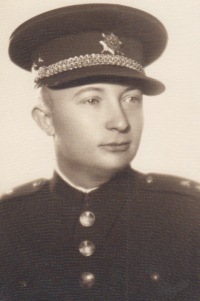

Marcela Míková, née Peštová, was born on August 3, 1942 in Sedlčany. Bohumil Pešta’s father served in the Czechoslovak army before the Second World War. During the war he commanded one of the units of the partisan group Death of Fascism. In May 1945, he disarmed German soldiers in Vysoké Chlumec near Sedlčany, then he was transferred to Sokolov. In 1948, he was transferred to the garrison in Žatec, where Marcela started going to first grade. Bohumil Pešta was involved in the anti-communist resistance group Prague – Žatec. On March 9, 1949, Bohumil Pešta was arrested in Podbořany and sentenced to 25 years in prison. He served his sentence in Bory, Mírov, and Leopoldov prisons and spent most of his sentence in Bytíz. In 1952, the family was evicted from the military apartment in Žatec, the mother moved with her two children to Příbram, Marcela continued her schooling in Sedlčany. Here they refused to take her to any secondary school, so she entered the secondary economic school in Příbrami. In May 1960, fourteen days before Marcela’s graduation, Bohumil Pešta was released from prison as part of an amnesty. Marcela started working in a brewery in Vysoké Chlumec after graduation, got married in 1961 and had two sons and a daughter. In the years 1961–1963, she worked at the ČSAD, and after maternity leave at the present-day Legionary Gymnasium in Příbram in the years 1967–1974. From 1976 until her retirement in 1997, she worked as an administrative worker and accountant at the Secondary Technical School in Příbram. She still lives in Příbram, he already has seven grandchildren and one great-grandchild.