They said no one needed a costume designer. That there was class struggle and people had to work

Download image

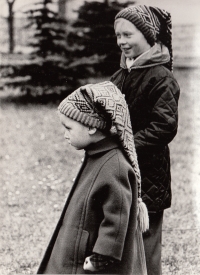

Emílie Milerová was born April 11, 1936 in Modřany near Prague to Helena and Václav Dlouhý. Both her parents came from poor families, her father was a bricklayer, her mother a lacemaker and embroiderer – she handled wealthy people’s clothes. Emílie had a sister who was ten years older than her and came from her father’s first marriage. She passed the war in Modřany with her parents. She remembers the May Uprising fights and the role of the Vlasov army in the liberation of Modřany. In 1950 she applied to study costume design but didn’t get a good reference – probably because she had refused to join the Pionýr (Pioneer). She completed a secondary school of chemistry but in the end didn’t devote herself to chemistry due to medical reasons and instead started working as laboratory technician in a hospital after studying at a school of medicine for two years. In 1959 she married the artist and animated movies director Zdeněk Miler whose children’s films are known by kids all around the world. She was a housewife for the following twenty-five years, raising two daughters and taking care of her overworked husband and also her granddaughter Karolína who lived at her grandparents from the age of fourteen. Milerovi were engaged in the dissent and were followed by the State Security. In 1982 her elder daughter Kateřina emigrated to Switzerland and returned back home after the revolution. From 1985 Emílie worked as a secretary at the Regional Institute of National Health but she retired after the institute had disintegrated in 1989. In her sixties she dedicated herself to her long-ago passion – painting. In 2001 her husband got infected with Lyme disease and his state of health began to deteriorate. He died in 2011. As of the time of the shooting, there have been ongoing civil litigations regarding the copyright to the work of her deceased husband.