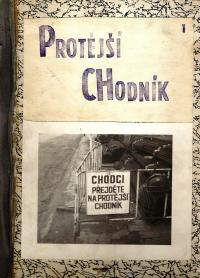

It’s not good to always choose the shorter route

Download image

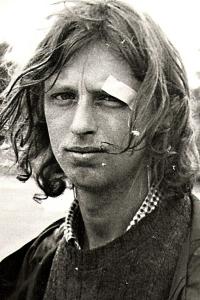

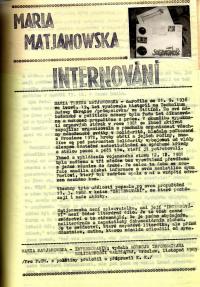

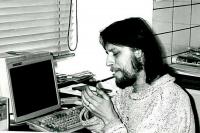

Ivo Mludek was born on 27 August 1964 in Opava. He grew up in Ludgeřovice, Hlučín District. His father was a worker at the Klement Gottwald Vítkovice Ironworks in Ostrava, his mother was employed in a school canteen. While attending the Secondary School of Economics in Opava, he was gradually introduced to Western rock music. He bought vinyls at swap meets in Ostrava, distributed recordings, and organised rock disco nights in the village around Opava and Hlučín. After completing the school he began compulsory military service with the Border Guards - he was stationed in Břeclav, and he witnessed the Communist regime’s diligent protection of the Iron Curtain. From the mid-1980s he worked as a stage hand at the Silesian Theatre in Opava and gradually built up connections with the Czechoslovak dissent and the Polish opposition. He distributed samizdat brought to Opava from Prague and helped publish the local samizdat magazine Protější chodník (The Other Pavement). In December 1988 he signed Charter 77 and was subsequently subject to regular detainment and interrogation by State Security. In November 1989 he became a leading figure of the Velvet Revolution in Opava. In early 1990 he refused to enter into politics and instead co-founded the newspaper Region.