You need to get along with the working class, they told her, and sent her to the assembly line

Download image

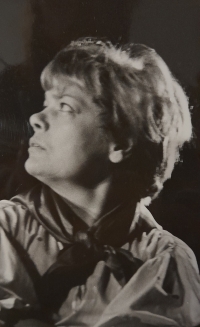

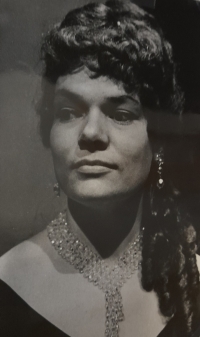

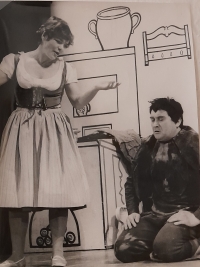

Hana Moravová, née Merunková, was born on the 9th of March 1935 in Lysá nad Labem as the fourth child of the confectioner Josef and his wife Růžena Merunková, née Martínková. They had five children, the firstborn was Josef in 1925, and the last one was Růžena in 1940. The family lived in a house on Bedřich Hrozný Square, where her dad built and set up a confectionery workshop with a shop in the 1920s. Hana Moravová is a contemporary witness of life during the Protectorate in Lysá nad Labem, where she attended the municipal and town school. She remembers the running of the confectionery, the school, the Jewish inhabitants, and how at the very end of the war in May 1945, the mayor František Tichý saved her brother from being shot by the Germans. In 1945, her father’s confectionery was transferred to a cooperative. Josef Merunka died in 1948 at the age of only 53 from heart disease. Hana Moravová graduated from grammar school in Nymburk in 1952, but because of her “entrepreneurial origin,” she was not recommended for university and had to choose one of three possible jobs. She worked in an office at Tesla in Libeň. In 1956, she reacted positively to the attempted revolution in Hungary and was reassigned to the assembly line as punishment. In the 1950s and 1960s, she was an actress in the Tyl amateur theatre in Lysá nad Labem, but she also performed in the Máj theatre in Prague and sang with a jazz dance group in Nymburk. She tried her luck at DAMU (theater university), but her first failure in the entrance exams discouraged her. She brought her younger sister Růžena Merunková to a professional acting career when she prepared and brought her to audition for the E. F. Burian Theatre. She worked in Prague’s Konstruktiva and from the mid-1970s as a clerk at the Ministry of Fuel and Energy, where she worked until 1989. She was married twice and raised a daughter Iva.