I was at the development of a colour camera for Czechoslovak Television

Download image

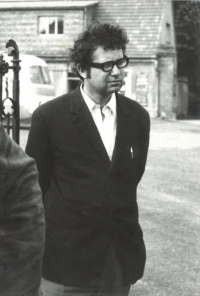

Ivan Mošna was born in Prague-Liboc on 26 July 1942. When he was six years old, his family moved to Dejvice, Prague. He graduated from eleven-year school, and after compulsory military service he joined the Radio and Television Research Institute in 1961 as a laboratory technician. At that time he began to study at the university, the Faculty of Electrical Engineering, and after graduating in March 1969 he started a scientific postgraduate course. At the research institute he participated in the development and production of a colour camera. He was a member of the Communist Party and wanted to leave it, but was not allowed to. In 1977, he submitted his dissertation, but was not recommended to defend it, so he did not defend it until after the fall of the regime in 1990. Shortly afterwards he left the research institute, then worked for two years in a private company, Epass, and eventually set up his own business with his son and a colleague. In 2024 he was living in Prague.