They wanted to criminalize me at all costs

Download image

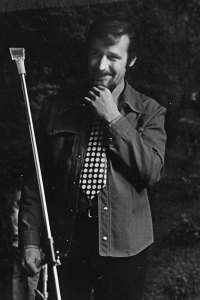

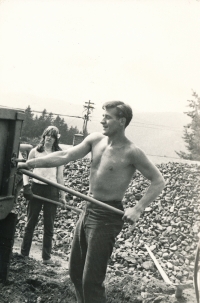

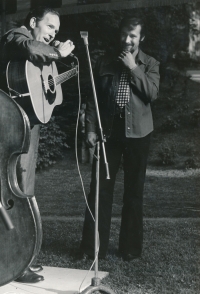

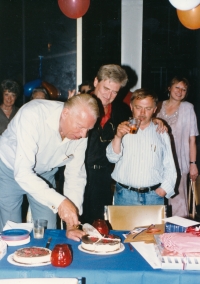

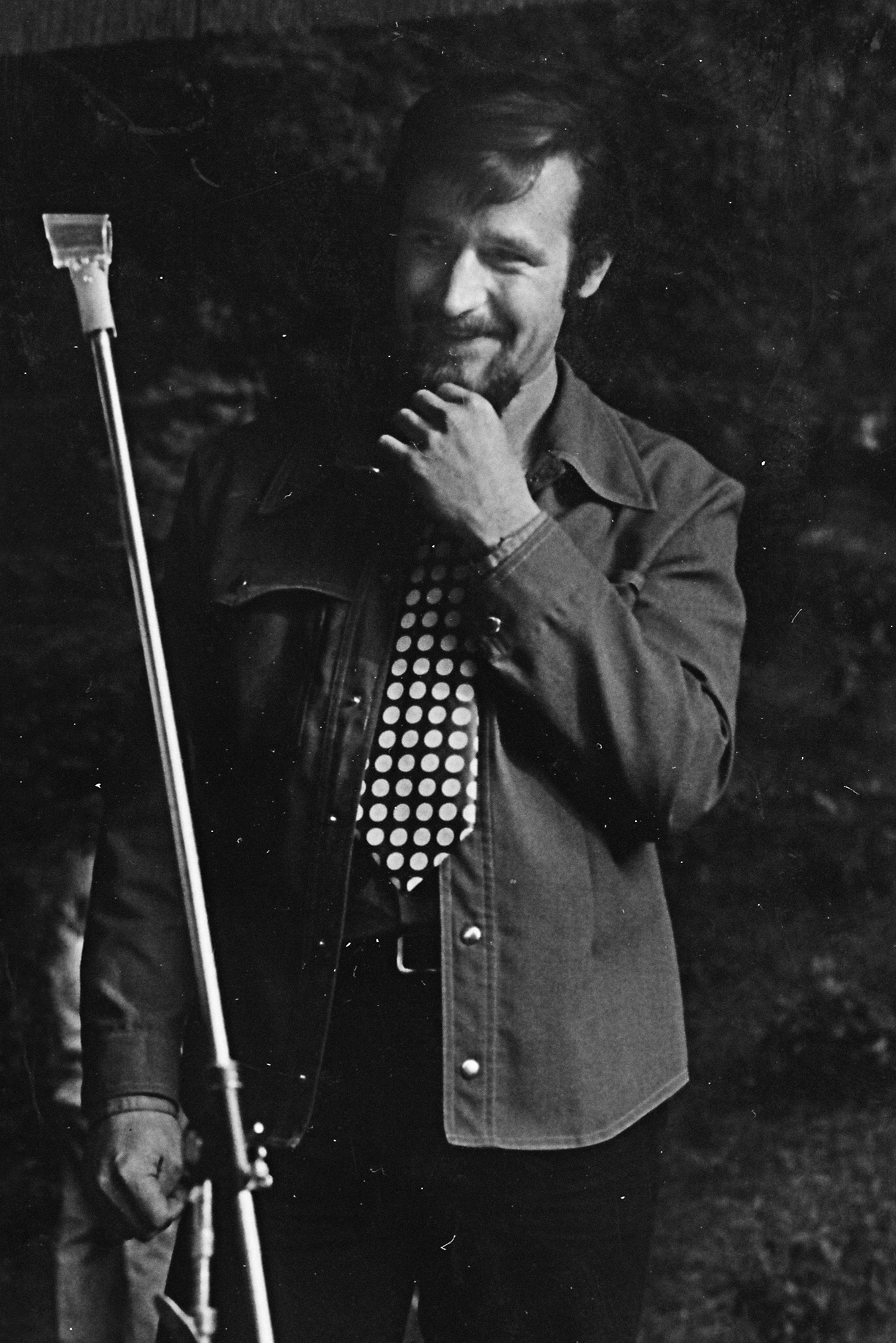

Josef Motyčka was born January 14, 1944 in Prague. His father died of tuberculosis when Josef was six years old. His mother then placed him into a children’s home because as a single mother she didn’t have time to take care of him. She died of cancer several years later and Josef’s older brother became his guardian. Josef studied at a hotel school in Mariánské Lázně and later at the University of Economics in Prague. While studying, he started working at the Czechoslovak Youth Federation and thanks to that he went on a business trip to the UK. Ever since then he maintained contacts with the International Voluntary Service organization, established by the UNESCO. The height of their cooperation were two international working camps in Mariánská near Jáchymov. In the summer of 1968 Josef managed to arrange for work placements in the UK for eight hundred Czechoslovak students. He tried to do that again the next year but the arrangements went awry just a few days before the departure because of the Czechoslovak government which banned the event. The ‘Květy’ and ‘Rudé právo’ magazines subsequently printed a series of inaccurate articles in which Josef and his colleagues were called crooks. Several lengthy trials made Josef and his wife attempt to emigrate. However, when departing from Budapest they were both arrested, sentenced and imprisoned for six months. After their release Josef worked as a laborer and manager of the Greenhorns band, which performed under the name Zelenáči during the Normalization period. In 1984 his wife Eva and their son applied for and were granted political asylum in the USA. One year after that Josef was expelled from the country to join them under the Sanitation operation. After the collapse of the Iron Curtain the family gradually returned back to Prague and became the instigators of the first student foreign exchange programs to the USA. In mid-1990s Josef found his name in the so-called Cibulka lists of State Security agents. Josef went to the Municipal Court in Prague which ruled in his favor and delivered a judgement that disproved any cooperation with the State Security.