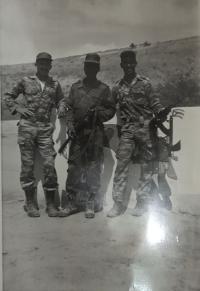

“When the Cuban regime began [its presence in Angola], of course it was without any knowledge of the Cuban people. The Cuban people only learnt about the participation of the Cuban troops in the Angolan conflict many years later. The conflict began in 1975. But the Cuban forces had been there since before, training the future Angolan armed force, and approximately around the year 1978, 1979, or 1980, it was made publicly known. It was when the Cuban regime led by Fidel Castro publicly announced the presence of Cuban troops there, directly linked to the conflict of the People’s Republic of Angola. Well, the process of recruitment to take the troops to Angola, as this Cuban adventure saw some 500,000 soldiers pass through there, as there were permanently around more than 50,000 Cuban soldiers stationed there, equipped and armed for all the military resources that are needed to carry out an adventure like this for 13 years. And this recruitment process was arranged in many ways. First of all, there was recruitment from the already existing military units, it was a way of recruiting or taking the troops to Angola – they raised the military units and gave them the mission to go to the People’s Republic of Angola. And they did it in a simple way. They took the unit, they loaded up the combat equipment in a port, and the rest of the troop either mobilized in boats or in airplanes, generally in airplanes of the Soviet airline Aeroflot. Another form of recruitment was through military reserves, where they interviewed you. If you agreed with the recruitment, there was no problem, but if you did not agree, they humiliated you, yes, I have to say it – they humiliated you... Even more, through the work centers and your own place of birth, where you grew up, in your own neighborhood, in your block, the Communist party organized meetings to get to know the reason of refusal, why person was not willing to fulfill an internationalist mission. And another of the forms was through the recruitment of boys who actually went to military service – they gave them a commission to go to the People’s Republic of Angola to fulfill this mission. Many of them did not have any idea what they were going to face. Many of those who were recruited, and the great majority was recruited and went to the People’s Republic of Angola under pressure by the regime itself, others were as adventurers, others went to meet their needs... So many of these, the immense majority of the recruited soldiers, went to fulfill their needs, the material ones especially, that the Cuban regime could not solve, that Socialism in Cuba did not solve, such as clothes, shoes, electrical household appliances etc.”