We are a generation that has been robbed of our ancestors

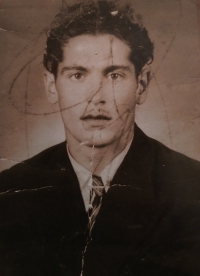

Rudolf Murka was born on October 28, 1959 in Novy Jičín. On his father’s side, he comes from a family of settled Moravian Roma and from his mother he belongs to the Sinti (nomadic Roma living mainly in Germany and on the territory of Czechoslovakia in the Sudetenland). His father Rudolf Murka (*1926) came from eight children and lived with his parents before The Second World War in the village of Veselá near Slušovice. Other relatives lived in Újezd, where the general family consisted of 25 adults and 25 children. After The Second World War, only six family members returned from concentration camps – in addition to Rudolf, his brother Antonín (who together with Blažej Dydy escaped from the camp in Hodonín near Kunštát and joined the partisans in Vizovice) and relatives Vlasta, Zdenek and Hedvik István and Otakar Herák. Father Rudolf was transported to the KT Auschwitz in March 1942, where he got to work in the main camp, while his relatives ended up in the Gypsy camp in Březinka and they all died. He also travelled to Buchenwald, Flossenbürg and with the death march he reached Terezin shortly before the end of the war. After the liberation, he settled in Želechovice and later in Mohelnice, because the houses where he and his family lived before the war were already flat compared to the ground. It took a long time for Rudolf to be reunited with his brother Antonín, who spent the last months of the war as a member of jan Žižka guerrilla group (he participated in events in Prlov and Ploská) and participated in the liberation of Vizovice. The witness’s mother Viktoria Murková, née Kryštofová, came from Bernartice nad Odrou, where her parents lived in nomadic cars and had a home there. However, after the border seizure, they were expelled, and in May 1939 (probably on the basis of a decree of the Ministry of the Interior, which urged the protectorate police to solve the so-called Roma issue), their property was auctioned off. They were saved from death in a concentration camp by asylum in Slovakia. In the village of Popudinská Močidľany they gained their home right and thanks to this they survived the Second World War. Of his mother’s relatives who remained in the Protectorate, only Uncle Alois Kryštof (*1928), who passed through Auschwitz (served at Sonderkommando), KT Dachau and survived the death march, survived. Out of a total of about 6,500 Roma living in Bohemia and Moravia during the Protectorate, about a tenth returned after The Second World War. For survivors and especially their new families, this meant, overwhelmingly, the total absence of a generation of grandparents and a large proportion of uncles, aunts and their children. Many of the witnesses’ relatives died in the gypsy camp in Lety near Písek and Hodonín near Kunštát, especially small children, and the rest of the family mainly died in Auschwitz. From the 1970s, when it became a matter of compensation for victims of the Holocaust, the Murkos began to visit reverent places in Lety and Hodonín, as well as Auschwitz. Rudolf grew up first in Nový Jičín, later in Gottwaldov, where his other siblings were born gradually. In total, there were eight children at home. His father worked as a driver of ČSAD and then for many years as an asphalter in The Building Works. My mother was a housewife. In 1968, after the Warsaw Pact troops invaded Czechoslovakia, the family considered emigrating. Although the Murkos did not leave in the end, a number of relatives decided to start a new life, especially in Germany. Before 1989, the witness’s mother traveled to Germany after the death of her sister to care for her children. At the end of the 1970s Rudolf also got a job with The Building Works. After the wedding, he lived for twelve years in Slovakia, where he and his wife raised two daughters, and returned to Moravia after the division of the Republic. At first they lived in Rymice near Holešov, where Rudolf ran a pub and at the same time worked as a Roma advisor at the Education Office in Kromeriz. The witness is dedicated to documenting the fates of members of his family, he participates, for example, in the creation of a memorial in Lety near Písek and cooperates with the Museum of Romani Culture in Brno. In 2020 he lived in Otrokovice.