Sixty years in Canada

Download image

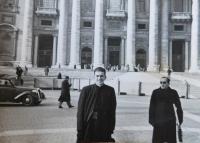

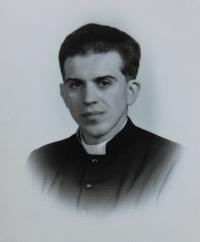

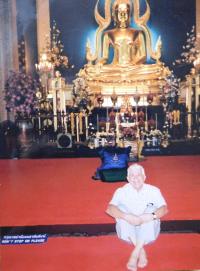

Jaromír Navrátil was born on August 24, 1924 in Dolní Dlouhá Loučka as the eldest of eight children. His father was a police officer and he and his family had to move frequently. Jaromír thus spent his childhood in several places in Moravia. He graduated from the trade academy and in early 1944 he and his fellow students with the year of birth 1924 were sent to Germany to do forced labour. Jaromír worked in an aircraft factory in the town Pössneck in Thuringia until December 1944. After the war he taught at the Masaryk Elementary Special School in Hodonín. After February 1948 he knew that he would no longer be allowed to do his job freely. He therefore decided overnight that he would escape to the West and in October 1948 in the Šumava Mountains he crossed the border to Germany together with a group of smugglers and about ten other people. Thanks to the invitation by the Catholic congregation of the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate he eventually got to Canada via Germany and Luxembourg and he spent about one year studying theology there. Jaromír then lived in several Canadian cities and he did many different jobs. He married Czech Ludmila Bouzová and he regarded Canada as his second home. Nevertheless, he missed his homeland and he eventually decided to return. Since 2010 he has lived in the Czech Republic again. Jaromír Navrátil died in 2019.