Prague is still the capital for me, even though I live in another country

Download image

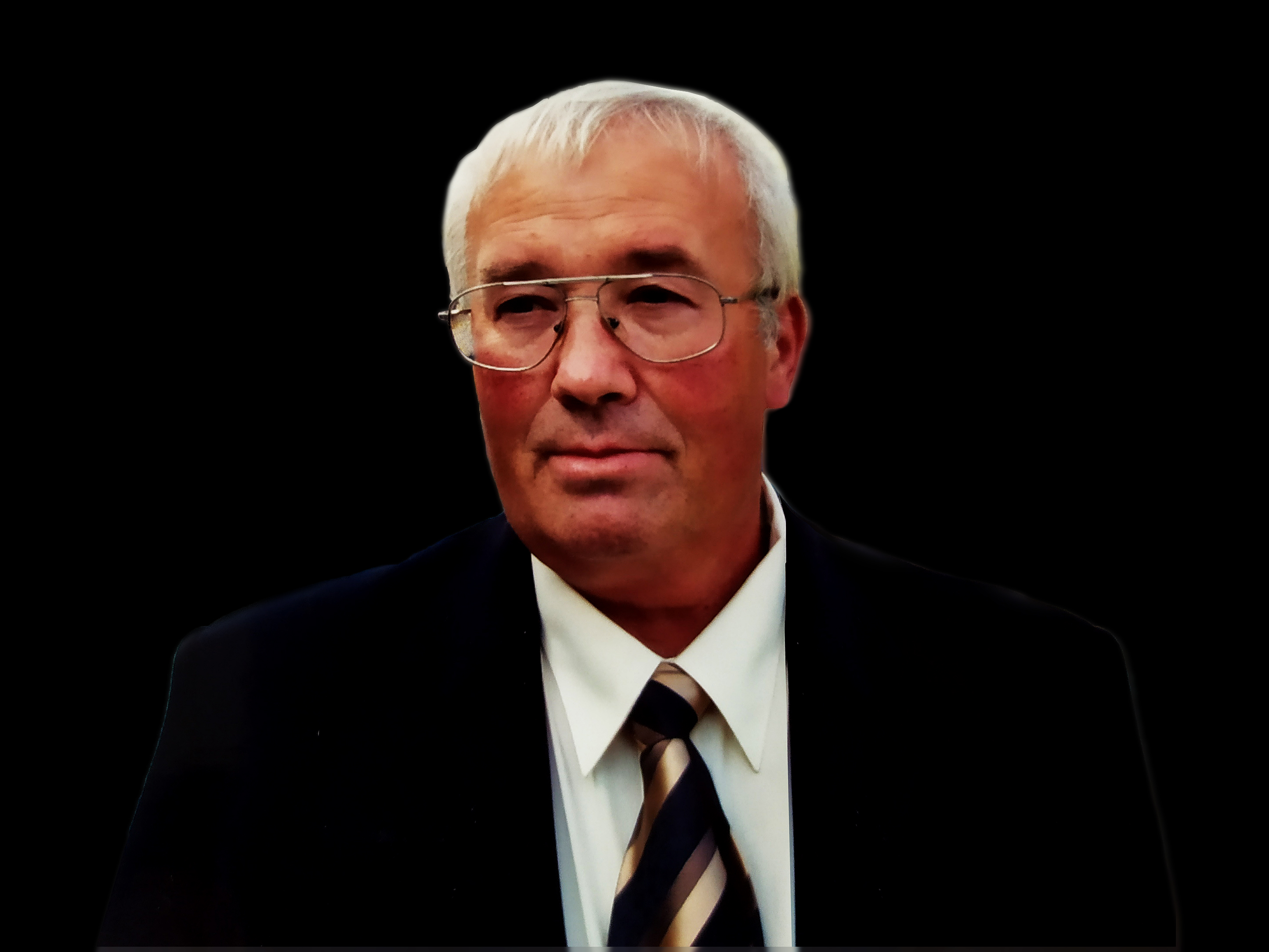

Jozef Német was born on 2 February 1951 in Michalovce, eastern Slovakia, the third of six children. His mother came from Handlová village, where she was injured in a bombing during the war. Her grandfather, with whom they lived, ran a shoemaking business. The communists forbade him to make new shoes, he was only allowed to repair the old ones, but this could not support him. Jozef’s father joined the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ) so that his children could study and he could have a better job as an electrical engineer. He remembers the joy when Yuri Gagarin flew into space in 1961. Jozef Német graduated from the primary school in Michalovce and the secondary industrial school in Humenne. He won a national competition with the school volleyball team in 1968. He graduated from the Faculty of Chemical Technology of the Slovak University of Chemistry and worked in the production of ceramics in various factories in Slovakia. In his third and fourth year he completed the so-called military preparatory school, and after graduation he enlisted for only one year. He spent a month in Podbořany and the rest in Cheb. After his return, he worked in the Kerko company in Tomašovce and then in a small majolica factory in Pozdišovce. As a non-partisan, he was not allowed to hold managerial positions, and he did not get the position of foreman until just before the revolution. During communism, he was nominated as a people’s judge and served for four years. For a long time in the east of Slovakia, they did not suspect that the communist regime might collapse, the first swallow was the candlelight demonstration in Bratislava in March 1988. He took part in public meetings and company meetings with the management. In the first free elections he was elected a deputy of the Slovak National Council for the party Public Against Violence. After the end of his mandate he worked in a wholesale grocery store. He remembers with regret the division of Czechoslovakia and still considers Prague his capital, where both of his children live. For the last 25 years he and his wife ran a newsagent’s shop, but he is now retired. He lives in Slovakia in Michalovce.