“I knew my wife and children needed me and I desired to meet them again. I really believed in it. It gave me a sort of mental strength to survive the Jáchymov hell.”

Download image

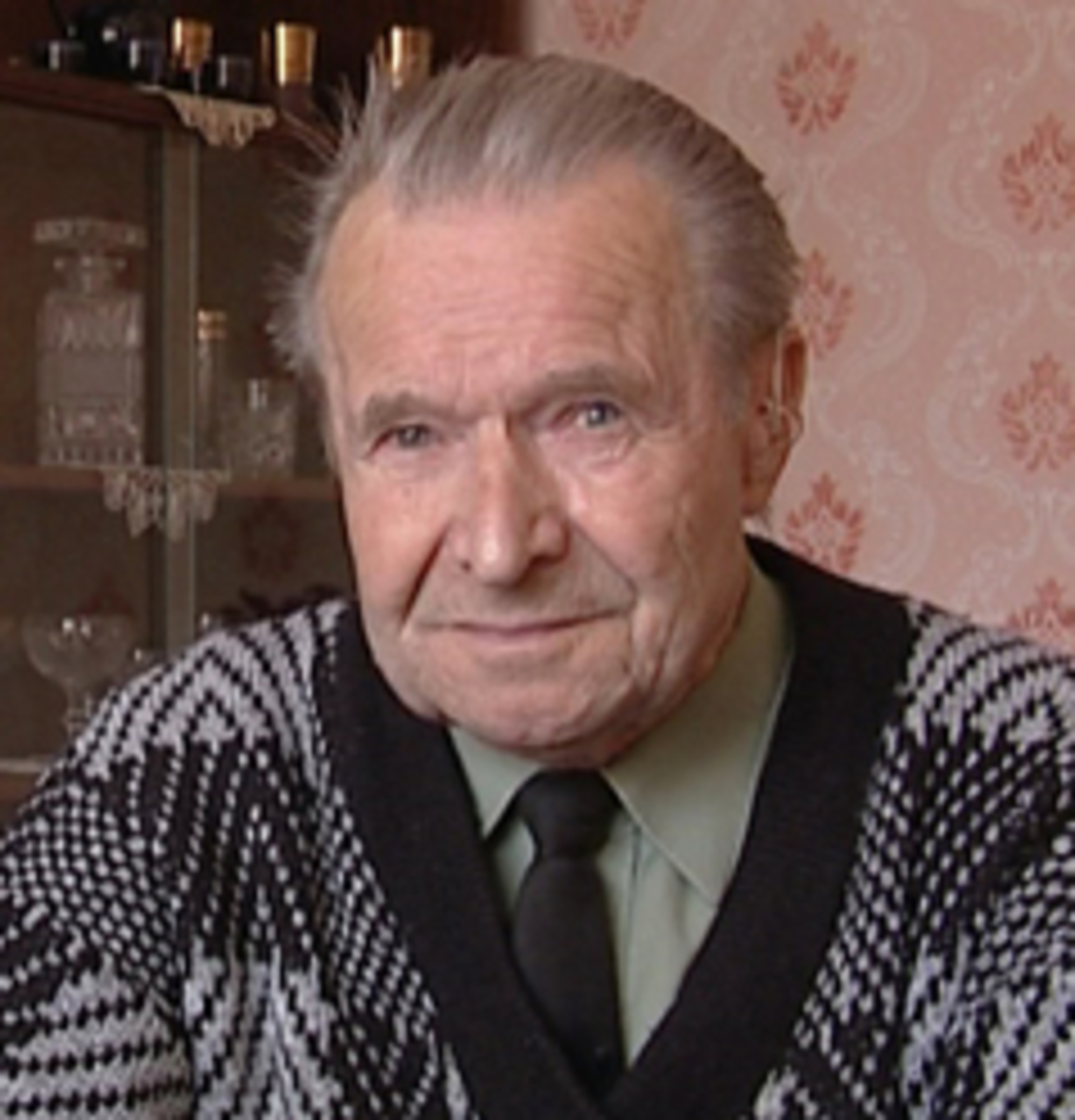

Jozef Nemlaha was born on February 27, 1925 in Malé Košecké Podhradie near Ilava. His father worked as a local blacksmiths and his mother was a housewife. Jozef finished the public and also municipal school and in the years 1940 - 1944 he studied to be a tradesman. He completed the courses of decorating and accounting and correspondence, thanks to which he managed to find a job as a wages clerk in Škoda enterprises in Dubnica nad Váhom. He spent the last months of the war in the house of his parents, where the two Jewish families were hidden from the horrors of the murderous Nazi regime. In summer 1945 Jozef Nemlaha got the job as a manager in the general store in Horné Sŕnie, where he also met his wife. In 1946 he got married and moved to the near village of Hloža, where he worked as a manager in the Food Cooperative, the shop, and the local tavern. Jozef’s father in law returned from America in 1947 and for the money he was sending home for those long years his family managed to acquire a modest property. He also helped his daughter and Jozef, her husband, open their own shop in Ilava, what actually was Jozef’s biggest dream. However, the seeming affluence attracted the attention of the incoming regime and Jozef was under the constant surveillance of the State Security. He wasn’t granted a loan from the bank, which he needed to buy a house, then, in July 1948 he was deprived of his driving licence for motorbike, after the February 25, 1948, the time of validity of his gun licence wasn’t extended, and thus only a year later his legally possessed gun was taken from him. Additionally, in December 1949 his merchandise and shop equipment worth 80,000 crowns were impounded. His private business was taken by the consumer cooperative called Budúcnosť (Future) in Žilina. He gained his profile of a very dangerous member of the socialist society, a diversionist, and a spy also due to his friendship with Pavol Gregor, who emigrated in 1949 and three years later came back to take his wife and daughters with him. In the evening of March 29, 1952, when Jozef was on the way from work, the State Security members arrested him and took him for an interrogation. Later, they slapped handcuffs on him and blindfolded him and transferred him to the prison in Ružomberok. The cruel investigation and physical as well as mental torture followed. The trial was held on July 20, 1952, then, Pavol Gregor was sentenced to death, Jozef Nemlaha was given the life imprisonment, and the others were sentenced to less than 10 years of imprisonment. All the convicts appealed against the judgement to the Supreme Court, which confirmed the qualification of their offence (espionage, § 86), but changed their sentences. Gregor was given the life imprisonment, Nemlaha seventeen years, and the others from 1 to 8 years. In addition to the imprisonment, Jozef Nemlaha was sentenced to the forfeiture of his property, the loss of his civil rights for ten years, and the financial penalty of 20,000 Czechoslovak crowns. However, the judgement also severely affected the lives of all the members of Jozef’s family. In January 1953 he was transferred by train from Ilava prison to Jáchymov camp Nikolaj, where he worked hard in the mine Eduard. Three years later he was transferred to the camp Rovnost, where he was forced to work in a radioactive environment without any protective equipment and where he was always hungry and physically and mentally exhausted. Forced labour and prison routine left traces on his health, so he was moved to the surface works into the cabinetmaker’s workroom and in 1959 into the correctional labour camp in Minkovice near Liberec, where he worked as a stone grinder. Thanks to the presidential amnesty of 1960 he was released from prison after eight years of imprisonment. He strived for the revision of his trial for a long time; however, he didn’t achieve the justice. Despite everything he experienced, he never abandoned his faith, love to his closest relatives, and his dream of justice and freedom.