Mom wasn’t just risking her own life, but mine too

Download image

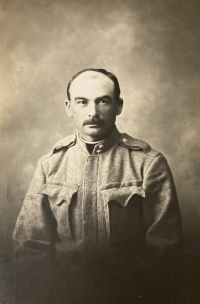

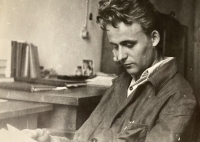

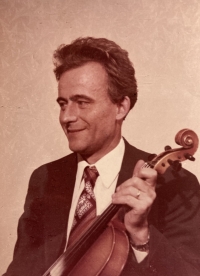

Marie Neumannová, née Svobodová, was born on April 2, 1935 in Berehovo, Transcarpathia. In 1920, her maternal grandfather Josef Tichý settled there after his return from the Russian legions. Her mother Marie Tichá graduated from the Ruthenian gymnasium in Berehovo, learned Hungarian and Ukrainian and became a very active Sokol member. In 1933 she married Alois Svoboda, who worked there as a clerk for the Czechoslovak Tobacco Directorate, and they had two children - Miroslav and Marie. Thanks to their father’s transfer to Moravia, the family did not experience the Hungarian occupation and lived through the Second World War in Hodonín. Marie Neumannová took away many strong experiences from this time, from minor clashes with the Hitler Youth to the devastating bombing of Hodonín on 20 November 1944. However, the greatest threat to the family during the occupation was her mother’s involvement in the anti-Nazi resistance. Marie Svobodová, brought up with Sokol ideals, worked as a liaison in the Blaničtí rytíři partisan unit: on the one hand, she secretly crossed to Slovakia and supplied the partisans in the White Carpathians, and on the other hand, she travelled to Vienna and brought messages written in invisible handwriting on cigarette papers. For better cover, she took her little daughter Maria with her several times. The end came only when she was denounced and then arrested by the Gestapo. They couldn’t prove anything against her, but from then on, she only distributed anti-Nazi leaflets. Her father was also arrested by the Gestapo for anti-German activities in the factory. He was imprisoned for six months and then assigned to work in Kukleny near Hradec Králové. After the liberation, the family moved to Strážnice, where her father became the director of the tobacco purchasing office at the Hodonín tobacco factory. However, the communist coup in 1948 brought many changes—her father was demoted to a lower position, her mother was expelled from the party, and despite her excellent academic performance, Marie was not admitted to grammar school at the age of fifteen. She eventually studied at a business school and, in 1952, moved to Brno to work as an accountant at the local arms factory. Her husband, Leo Neumann, became a recognized expert in nuclear fuels and radiochemistry and taught at the University of Chemistry and Technology in Prague. He never joined the Communist Party, which complicated his career advancement and his ability to secure an apartment. As a result, Marie had to stay alone with their children in Brno for several years before she could move to join her husband. At the time of the interview in 2024, Marie Neumannová was living in Prague.”