Dad threw the red book of the JZD agitators on the floor

Download image

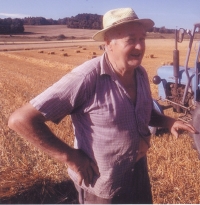

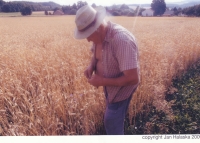

František Novák was born on 21 January 1934 in Brandlín, South Bohemia. Both of his parents came from farming families and owned small farms. During World War II, they had to hand over their food supplies. Like other farmers, they tried to keep at least something for themselves. For example, they used to secretly grind grain but they had to look out for ubiquitous German controls. In 1944, they observed how one of the planes from the Union, which was flying over Brandlín to bomb Pardubice, dropped several bombs by accident. At the end of the war, German refugees and members of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army appeared in the area and robbed potatoes from their cellar at night. Later came the German captives who had to work for the farmers. The witness’s father joined the Communist Party in 1946 out of enthusiasm. When they started repressing farmers and agitating them for joining the Unified Agricultural Cooperative, he threw the Communist Party card on the floor. In addition, he refused to join the JZD [the Unified Agricultural Cooperative - transl.]. In return, they took his fields from him, and he was allotted distant fields and fields with stony soil instead. In addition, they admeasured him a huge supply of food. The witness apprenticed as a butcher and worked in the Satrapa butcher factory all his life. He never in his life voted for Communists and never joined the Communist Party. He was a deeply religious evangelical and attended church every Sunday. In 1968, he joined the demonstration against the August occupation. He listened to Radio Free Europe, where he got information about politics, dissent or Charter 77. During the Velvet Revolution in 1989, he participated in all the demonstrations in the area. In the new era, he regained the family lands in restitution and continued to farm privately. In 2022, he lived in his house in Brandlín.