I was a lucky man

Download image

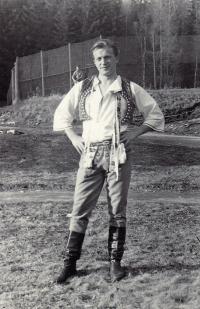

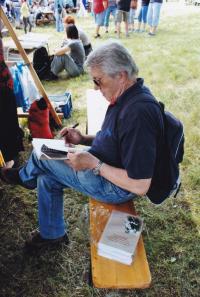

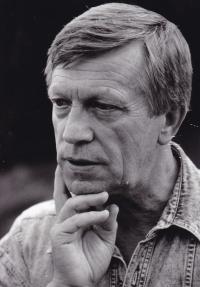

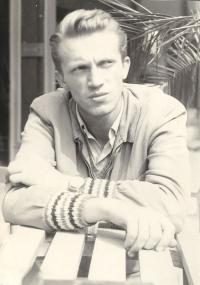

Jan Pavlík was born on 8 July 1937 in Kuželov in Horňácko (Hodonín District). His parents owned one of the largest farms in the region and a shop, so the witness had “kulak’s son” written in his cadre report (political profile) following 1948. His folklore activities helped enrol at a grammar school in Strážnice and later at the Faculty of Medicine in Brno. He was active in the folklore movement. In 1960 he married Marie Vránová. After graduating from medicine he was employed at the hospital in Hodonín. By his own request he transferred to Čejkovice in 1964, where he helped organise the construction of a new medical centre; he succeeded in saving the local castle from demolition and established the folk ensemble Zavádka. In 1976 he moved to Kyjov for family reasons; he worked at the local hospital and participated in folklore activities in the region. He worked in the programming boards of the Strážnice folklore festival, Slovácký rok in Kyjov, Horňácké slavnosti; he sat as a judge in contests for the best dancer of the Moravian Slovakian “verbuňk”. As a doctor, he specialised in angiology; he started a private practice after the revolution. Over the years he also wrote several books - novels, monographs, and poetry collections. In 2017 he received the Mayor of Kyjov’s Award.