I told everyone everywhere what I thought. It was my war

Download image

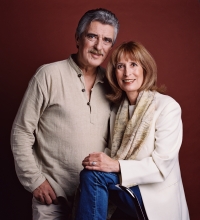

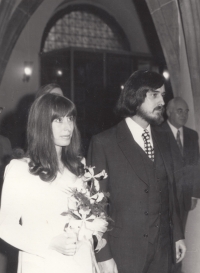

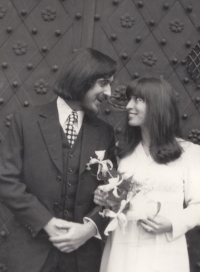

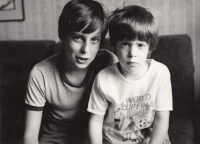

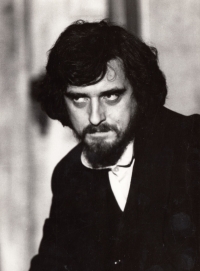

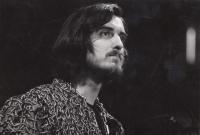

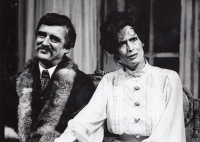

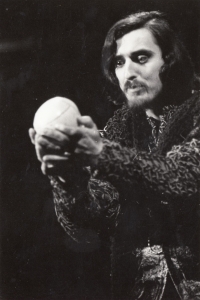

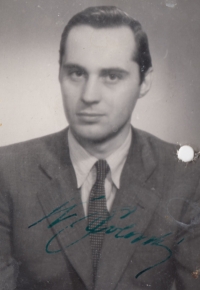

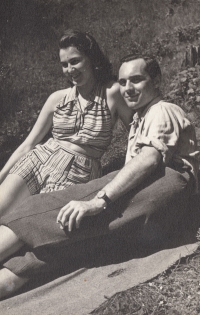

Pavel Pavlovský was born on December 11, 1944 in Prague to a middle-class family. He graduated from an eleven-year high school, after which he was admitted to DAMU in 1962. Already during his studies, he stood alongside the big bards, among other things, at the National Theater. In 1966 he joined the J. K. Tyl Theater in Pilsen. From 1966 he also completed two years of military service. He spent the first year with the Army Art Ensemble in Prague, the second at the airport in Líny, where he could play theater. It was his first time at that time. He experienced the arrival of the planes of the occupying troops at the airport in Líny in 1968. In the same year, he starred in the famous film Všichni dobří rodáci (All the Good Natives). He tasted the free theatrical environment of the sixties, but also the taste of plays promoting the enthusiasm about the communist regime. The National security interrogated him several times in Pilsen and Prague, but he unequivocally rejected their offer to supply information from artistic circles. Years later, he discovered that his name was on the list of people destined for economic liquidation in the project Norbert. From 1971 to 1972 he worked at the Za branou Theater, then for ten years he was again engaged in the J. K. Tyl Theater. In 1974, he got married for the second time, with the actress Monika Švábová. From 1982 to 1989, he worked as an actor at the Realistic Theater in Prague, and after its termination he returned to Pilsen again and permanently. The day after the brutal suppression of the student demonstration on Národní třída on November 17, 1989, he read in the Chamber Theater a fundamental statement condemning the police intervention and urging a strike. From the first days of the strike, he served as chairman of the strike committee and moderated discussion evenings with spectators. In 1992, he was elected the head of the drama section in the J. K. Tyl Theater. In 1993, he was the first in history to receive the Thalia Award, and for his theatrical roles he was twice awarded the Czech Literary Fund Award. He created about 150 roles. His filmography and collaboration with radio are also significant. In 2011 he received the Historical Seal of the City of Pilsen and in 2014 he entered the Hall of Fame of the Pilsen Region. Together with his wife, with whom he has two sons, he created a number of fateful roles on stage and in life.