Not to let myself be broken

Download image

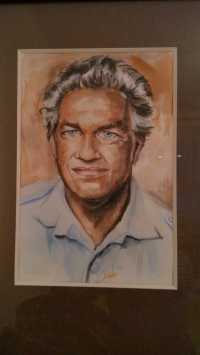

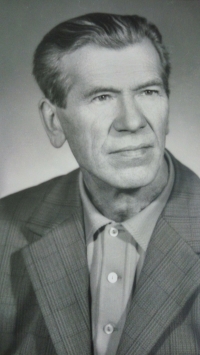

Marie Pešková, née Halašková, was born on 26th May 1937 at Kvasice near Kroměříž. Her father worked for the Bata company as a travelling salesman having a good position and a salary. During the war he helped parachutists, Marie does not know the details. He was arrested in the Heydrichiad and executed at the Kounicovy koleje in Brno on 29th June 1942. As Marie´s mother says - he was denounced by his best friend. Marie studied at secondary technical school for a year but worked most of her life at railway stations as a carriage dispatcher. Neither she nor her husband Emil Pešek were members of the Communist Party. Both received awards for excellent work and also medals for active work in tourism. The witness has never been afraid to fight for the right cause if she considered it a matter of justice be it a higher salary or a compensation from the Czech or German authorities.