They told me: You’re heading for prison! And they were right

Download image

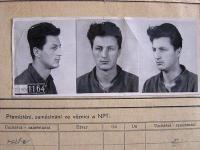

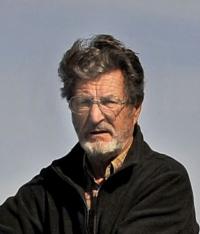

Alois Peyr was born on the 24th of March 1935 in Pilsen into the family of a telegraph clerk. His father’s job meant that the family was often on the move, finally settling down in Sokolov, where Alois completed a mining school. He wanted to continue his studies at the College of Mining in Duchcová, but he was not allowed to do so. He took part in small subversive activities, e.g. he distributed pamphlets. He was not satisfied with life in Czechoslovakia, as he felt he was constrained by the system - thus he decided to emigrate with his friend Jan Kuhn in December 1953. They were detained during their first attempt, however, by an East German patrol which handed them over to Czechoslovak soldiers. They subsequently succeeded in escaping. A few days later they made their second attempt, but were caught and taken to Karlovy Vary for interrogation. They were released on New Year’s Eve 1953. On the 19th of April 1954, Alois Peyr and Jan Kuhn tried to blow up the statue of a soldier in the Sokolov square. They were preparing for another emigration attempt when they were arrested. Peyr was interrogated for five months and then sentenced to nine years in prison. He was sent to the uranium mine Eva near Mariánská Camp. In 1956 he took part in a camp riot and was transferred to the Bory prison. He was released in 1962 and worked in manual labour. Following August 1968 he emigrated with his family via Austria to Australia. In his old age he sailed around the world in his yacht.