I would never let him go into exile alone

Download image

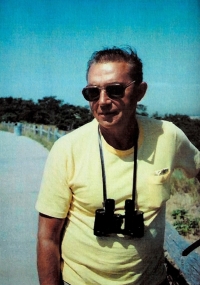

Marta Pinke, née Křivanová, was born on 2 April 1931 in Prague, Žižkov. Her father, Otakar, was a small businessman, very enterprising, who managed to run a fish salad shop during the war, despite food ration cards. After 1948, however, his business was nationalized and he was forced to go to work in the mines. Marta Pinke, after graduating from the burgher school, started an apprenticeship in a music shop. In 1960 she met former political prisoner Karel Pinke, who had just been released under the amnesty of President Antonín Novotný. Karel Pinke was arrested in 1950 together with his wife Milada Pinke and brother Miroslav Pinke for espionage activities and contact with the British secret service agent Jan Brejcha. He was given fourteen years, of which he served “only” ten thanks to an amnesty. In 1952, he cooperated with State Security for a few months and was placed in a remand prison, but soon ended his cooperation due to a nervous breakdown. As a political prisoner, he then worked in the worst conditions in the uranium mines in the Jáchymov and Příbram regions. His wife divorced him, he was seriously injured twice and for the last two years he was treated for open tuberculosis in Bory. He was released in 1960 at the age of forty-one. Marta and Karel Pinke married in 1960 after a short acquaintance. They welcomed the Prague Spring of 1968 with great joy, and Karel Pinke became a member of the newly established K-231 Club of former political prisoners. When the Warsaw Pact troops invaded Czechoslovakia on 21 August, he feared further imprisonment and decided to emigrate. His wife stood faithfully by his side. In August, the Pinke’s left for Vienna, where they waited in the Traiskirchen refugee camp for several weeks before their turn came in December and they were finally able to fly to Canada. In Ottawa, they gradually built a new life for themselves and became involved in local country clubs; Karel Pinke became mayor of the Ottawa Sokol and a member of the Sokol County of Canada. In the 1970s their citizenship was revoked and they were convicted in absentia for leaving the country. When the Velvet Revolution came to Czechoslovakia in 1989, Karel Pinke did not believe in regime change for long. It took a full ten years for the Pinke family to return to their homeland. After thirty-one years in exile, they settled in Prague again in 1999. Karel Pinke died after a long illness on 14 October 2007. For his meritorious work in Canada he was awarded the Miroslav Tyrš Medal and the Masaryk Award. Marta Pinke was living in her apartment in Prague’s Vinohrady district at the time of filming (in 2023).