We were eager to see what was happening in the world

Download image

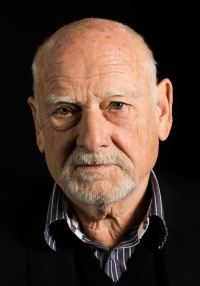

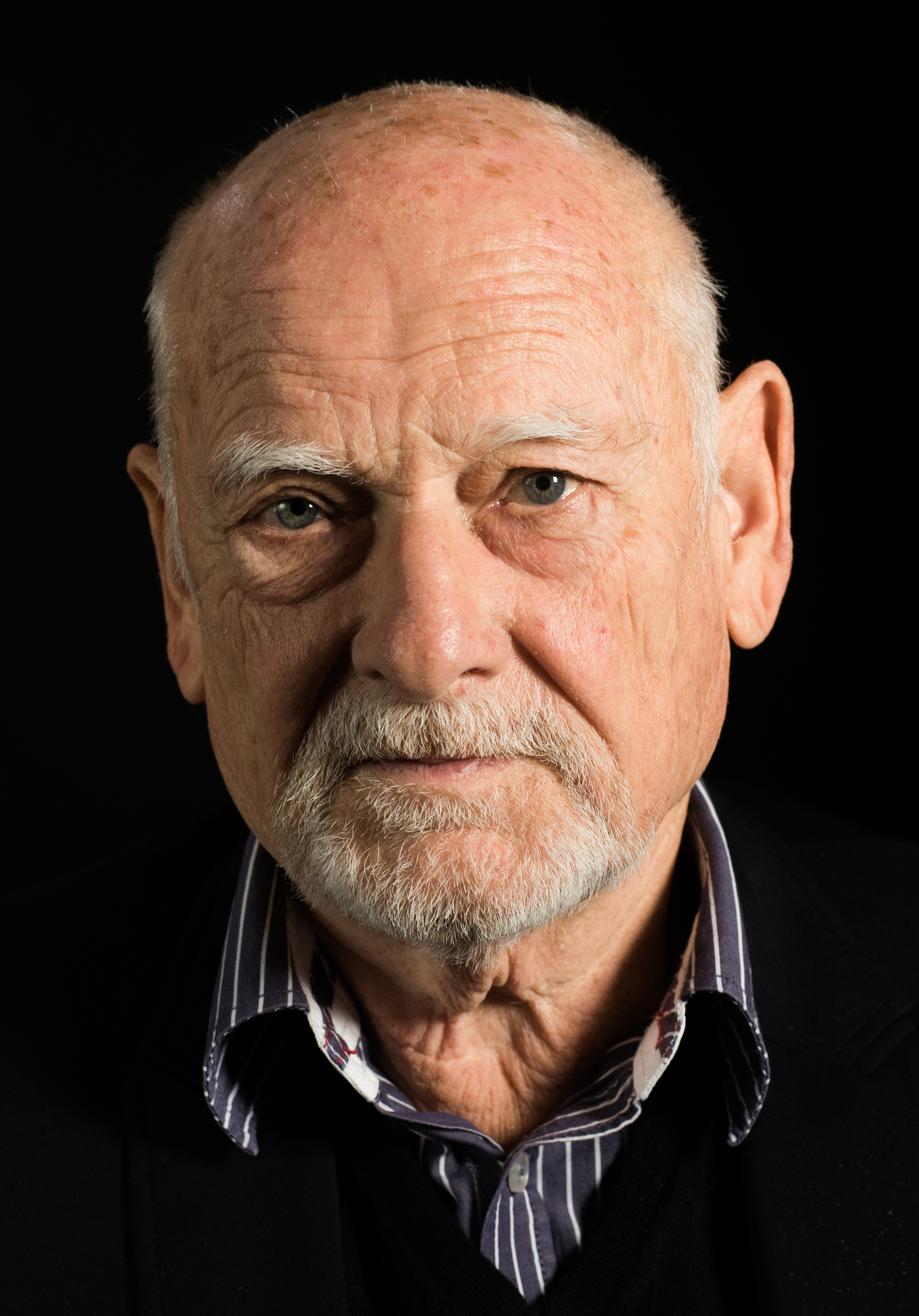

Theodor Pištěk was born in Prague on 25 October 1932 into an artistically oriented family. Both of his parents, Theodor Pištěk Sr. and Marie Pištěková, were well-known actors. His grandfather Jan Pištěk built and ran the ‘Pištěkárna’, the Pištěk Folk Theatre in Královské Vinohrady. His maternal grandfather Julius Ženíšek was an importer of Ford cars to Austria-Hungary and the son of the painter František Ženíšek. Theodor Pištěk Jr. grew up during the war and has dramatic memories of May 1945 when he witnessed the anti-Nazi uprising of the Czech people and the Revolutionary Guards in Prague’s Vinohrady. The Pištěks accommodated Major Patrick Dolan, the commander of the American mission that brought penicillin to Prague, in their apartment. In 1948, the witnessed transferred from a multi-year grammar school to the Higher School of Art Industry, thus escaping the subsequent State Security raid on a group of his former classmates who would meet for optional religious classes. From 1952, he studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vratislav Nechleba’s studio and, while a student, he was suspended for a year over writing a letter to a Dutch art school with a classmate inquiring about scholarship options. After graduating in 1958, he focused on painting and cinema. He became a reputed film costume and set designer, winning an Oscar in 1984 for his costumes for Miloš Forman’s Amadeus. In the 1960s, he was also a car racer and competed in the European Cup.