My family hasn’t experienced the horrors of gulags, but it has experienced the horrors of everyday life.

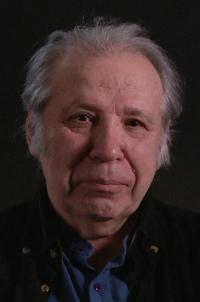

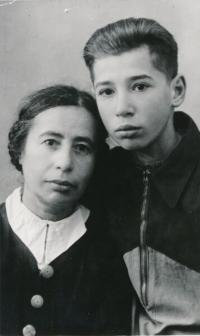

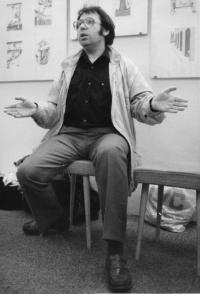

Viktor Pivovarov was born January 14, 1937 in Moscow. After completing his studies at a boys’ secondary school, where there were also some former guardsmen from gulags teaching there, his mother and uncle decided to get him admitted to an art school. There he had his first personal encounter with the regime, when in 1953 shortly after J. V. Stalin’s death he tore down several of his portraits from the wall, stuffed them behind a cabinet and used the frames for his own illustrations which he was to exhibit in the school’s halls. He was lucky for it was shortly before the 21st Congress of the KSSS, and thus he escaped only with a strict warning. After graduating from a secondary art school he first applied for the Moscow Academy of Fine Arts, but he was not accepted, probably because his leaning towards experiment and modernism was too evident. This, on the other hand, helped him when taking exams for the Faculty of Illustration of the Institute of Polygraphy, which was the most liberal school in Moscow. In the early 1970s he was earning his living by illustrating children’s books. He also began meeting a journalist from the Washington Post, who remains his friend till today. His friends were often interrogated for having contacts with journalists and diplomats, and Pivovarov himself was once visited by a KGB agent who tried - unsuccessfully - to have him join their ranks. In 1978 he met Milena Slavická, fell in love with her at the first sight and four years later he followed her to Prague. Fortunately, thanks to Jindřich Chalupecký he soon joined the artistic elite of that time. Moreover, unlike in Moscow, in Czechoslovakia he was allowed to exhibit his works: he had his first exhibition in 1983 in the ÚKDŽ building on Náměstí Míru in Prague, and in 1989, before the revolution, he had the opportunity to hold a large exhibition of some hundred pictures in Lidový dům in Prague-Vysočany. A great retrospective exhibition was held in the Rudofinum Gallery in 1996.