A lonely fight

Download image

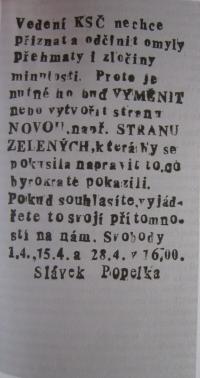

Jaroslav Popelka was born in 1956 in Uherské Hradiště. As a child, he witnessed firsthand that the communist regime is capable of destroying entire families. His father’s business was nationalized and the family was left to live in cramped and unsuitable conditions. Another example was his uncle, who refused to join the farms collective. For this, he was imprisoned and eventually died as a result of the drastic treatment had been subjected to. Jaroslav Popelka thus came to hate the communist regime already in his childhood and his resistance towards it was growing stronger and stronger. In the second half of the 1980s, he began to print and distribute leaflets calling for resistance and demonstrations against the regime. In 1988 and in 1989, he was imprisoned five times altogether for his offences against the public order. In prison, he held several hunger strikes, during which demanded the demise of the Communist Party. He’s not satisfied with the evolution of things after November 1989 and he’s still actively seeking political change.