I acted deliberately and knew what could happen.

Download image

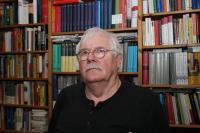

Gerd Poppe was a pioneer and an important representative of the opposition in the GDR. He was born in 1941 in Rostock. His childhood was marked by the aftermath of the war in a bomb-destroyed city. In 1947, he started attending school and throughout his school years he would feel a deep aversion to the constant presence of Soviet heroic stories and Stalin images. After graduation, he served a one-year apprenticeship as an assistant fitter in the Warnow shipyard in Warnemünde. Thereafter, he studied - respecting the wish of his father - physics in Rostock; in 1964, he finished his studies. From 1965 to 1976, he worked as a physicist in the Stahnsdorf semiconductor factory. Poppe sees the construction of the Wall in 1961 as the beginning of his dissent towards the system. Although his political interest grew stronger throughout the years, he still believed in the possibility of an evolution of the communist system and was looked heavily to East Central Europe, where he saw a greater measure of freedom. After the suppression of the Prague Spring in 1968, he signed the letter of solidarity in the Czechoslovak embassy. In 1970, Poppe moved from Stahnsdorf to Berlin, where he made many new acquaintances who shared his critical attitude towards the system. Through his friends he met Robert Havemann and Wolf Biermann. Poppe would refuse military service and had to serve six months as a so-called “construction soldier” (Bausoldat) in 1975. The expatriation of Wolf Biermann in 1976 was a turning point for Poppe: He addressed a protest note to Honecker, whereupon the Academy of Sciences withdrew its support for his employment. Henceforth, he was in fact banned from working and worked until 1985 as a mechanic in a Berlin swimming pool. After Biermann’s expatriation, Poppe also lost a large part of his circle of friends, as many emigrated to the West. In addition, many of his Trotskyist friends were arrested at this time and as a consequence, Poppe’s apartment was searched by the police. However, in this period, Poppe got to know a number of new people: the reading of Rudolf Bahro’s “The Alternative” in 1977 served as an inspiration for him. In 1979, Poppe tried in vain to persuade Bahro to withdraw his consent with his expatriation after release from prison. During this time, Poppe’s relationship with Havemann also intensified. After the lifting of his house arrest in 1979, Poppe would often visit him. The second half of the seventies were characterized by numerous political discussions in small groups held by Poppe; however, they were always held in the same sort of circles and thus had no effect on the public. At this time, he was still positioned left on the political spectrum, but by the end of the seventies, he had lost the hope for democratic reforms. Poppe would also keenly follow the situation in and make frequent trips to the Central and East-European neighboring countries, especially to Czechoslovakia and its Charter 77 movement. The activities in East and Central Europe served as an inspiration for him that was to be put into practice in the GDR as well in order to create a counter-public. The peace movement of the late seventies, which was unfolding predominantly in the ecclesiastical context, was extremely important for the beginnings of the opposition movement. Poppe too had numerous contacts with the international peace movement, but he never acted out of Christian motifs. Starting in 1980, Poppe would regularly organize literary seminars in his apartment. These were surveyed by the Stasi under the heading of “unapproved happenings”. Poppe was subsequently charged with administrative fines. In 1980, Poppe and some others founded an independent school for children, which existed until 1983, when it was destroyed by the Stasi. Already in 1980, Poppe could no longer travel; he had been blacklisted and would be always turned around at the border crossing. The more important became the meetings with international activists in East Berlin: In 1983, the contacts with the international peace movement became more intense; during the second END-Convention in West Berlin, their representatives paid a visit to the opposition in East Berlin. This first meeting was held in Poppe’s apartment, which developed in the following period into a major hub for international activists. In the same year, the contacts with the West German Greens were established - Poppe stayed in close touch in particular with Petra Kelly. The West German politicians were able to smuggle books, journals, letters, but also technical devices into the GDR, using their diplomatic passports. This support was important for the publication of illegal samizdat magazines in which Poppe was involved. In 1983, Poppe’s wife Ulrike was arrested along with Bärbel Bohley for “treasonable news transfer”. This triggered massive protests of the international peace movement that resulted in the release of the detainees after six weeks of pre-trial detention. Such a reaction of the totalitarian regime was a new phenomenon of the eighties: arrestees who had attained a certain level of international recognition were released after their arrest since protests were expected. Poppe himself, for instance, would always be arrested only for one day, to stop him from attending events (for example in 1979, the trial with Havemann). In 1985, together with Bärbel Bohley and Wolfgang Templin, Poppe founded the opposition group “Initiative for Peace and Human Rights (IFM)”. The starting point for the foundation of the group was a planned seminar on human rights, which was cancelled due to pressure on the parish in which the seminar was to be held. The IFM was based heavily on the content of the Charter 77 and on its peace concept of the balance between the inner and outer peace. The samizdat publications were very important in this context as they enabled a GDR-wide distribution and thus the linking of the various groups. The result was a network that also enabled the spreading of information about events in other countries or joint solidarity statements. Since the early eighties, Poppe was increasingly being surveyed by the secret security police. Since 1980 onwards, he was banned from traveling. Records show that in 1983, his arrest was being considered and since the mid-eighties, the Stasi tried to pressure and destabilize his family with the aim of forcing them to leave the country, however, it did not succeed in its plan. Since 1985, Poppe was able to work as an engineer in the construction office of the Diaconia. During the Revolution of 1989, he represented the IFM at the round table, being a member of the “New Constitution of the GDR” working party. In the Modrow government, in office between February and March 1990, Poppe was minister without portfolio. In the March 1990 elections, he ran for the Alliance 90 (Bündnis 90), which he then represented until October as a member of the freely elected People’s Chamber. In 1992, Poppe could see his file at the State Security. Throughout the years, he had been spied on by about 40 people. The IFM had been infiltrated as well, with up to six active informers at times. From 1990 to 1998, Poppe was Member of Parliament for the Alliance ‘90 /The Greens. After the 1998 elections, he became the first special representative of the federal government in the foreign-affairs ministry for human rights. He was thus able to take up his original commitment to the cause of human rights and foreign policy. Since 1998, he has furthermore been a member of the board of the Federal Foundation for the Reappraisal of the SED dictatorship.