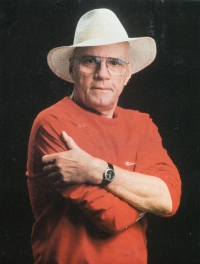

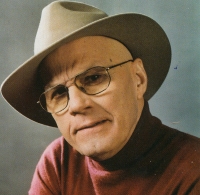

My father instructed me from prison and was a hero for me

Download image

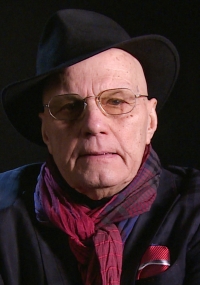

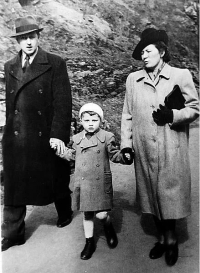

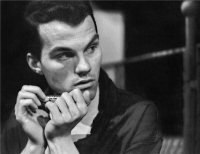

Jan Přeučil was born on February 17, 1937, in Pardubice. His father, František Přeučil, the owner of the Pamir publishing house and an MP for National Socialists, was arrested in 1949. He was sentenced for life in the Milada Horáková trial. His family had to move out of their flat. Jan was told at school that he must atone for his father’s guilt by becoming a labourer. He trained as a model maker, studied grammar school in the evenings and tried to get accepted to Theatre Academy (DAMU). Although he passed the entrance exams and had many recommendations he was not accepted due to his father’s imprisonment. He had to go to work in a foundry. Eventually, however, he graduated of DAMU. He became a member of the Divadlo Na Zábradlí. In the 1980s he joined the Communist Party, although he opposed communist ideas. He was convinced that in this way his life would be easier. He didn’t as the daughter of his wife, actor and host Štěpánka Haničincová, married Jiří Chmel who signed the Charter 77. The family was under constant surveillance of the Secret Police and Štěpánka Haničincová lost her job in Czech TV. After her death he married actress Eva Hrušková and together they stage performances for children. Besides that he does theatre, TV and film and also lectures to students.