The problem we have is that we are not able to appreciate freedom.

Download image

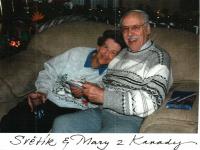

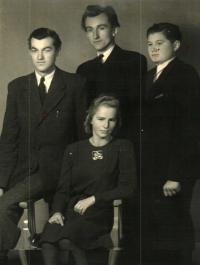

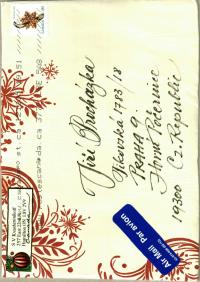

Jiří Procházka is an important representative of the Methodist church in our country. The roots of its missionary activities lie in the beginning of the 1920s with his father, Karel Procházka, being among the most important preachers. Before the Second World War, the Methodists in Horní Počernice were looking after an orphanage. Because his father believed that the future belongs to crafts, Jiří trained to be blacksmith, until being sent to forced labor in Modřany in 1944.His father was a member of the illegal resistance group Boj (“Struggle”) through which he and his friends distributed leaflets. They were supported even by baron Nolš, who officially claimed to be a supporter of the Nazi occupation. When Karel Procházka went to him to ask for money, he hid him so that a random Gestapo check that just arrived didn’t find him. Despite their activities not being disclosed, he was sent to Mauthausen for listening to foreign broadcast as a tenant owing money for rent turned him in. There, he escaped death very tightly, being saved by a friend. He witnessed enmity between Czech Communists and non-Communists, which was a matter of astonishment even among foreign prisoners.When the Communist repressions of churches started to intensify, the Methodists were deprived of their property too. Unlike many other priests, they managed to survive the repression without a bigger harm. The Communist authorities tried to persecute the church members directly in 1950, when they held two Methodist brothers for two months and wanted to destroy the church in the same way as in Hungary. Fortunately, it didn’t happen. But still, the church leaders had to make concessions and negotiate all the time so that the Communists approve the priests that wanted to join the body. As a result, many of them appeared on the State security list of collaborators. Jiří Procházka continues in his missionary work even today. He saw its beginnings, development, attempts to persecute it as well as the current state. Nowadays, he helps with the running of the asylum house for socially weak. Also, he works with children and tries to educate them in religious circles as well as in schools. Especially, he emphasizes the insufficiently appreciated role of freedom in our lives.