Democracy must be supported

Download image

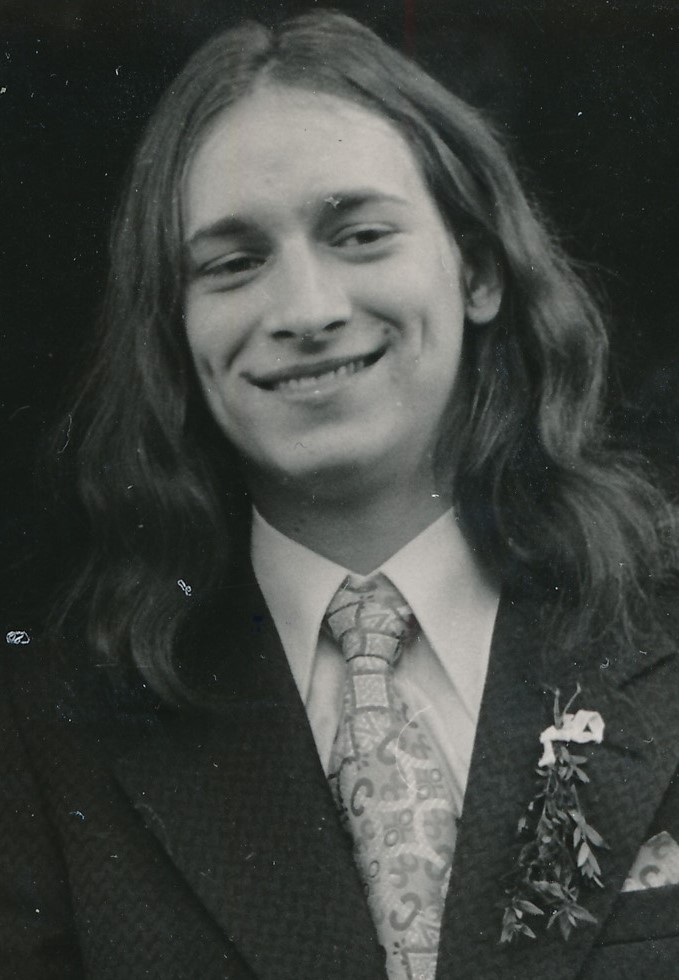

Jiří Prokop was born in Prague on 26 January 1958. His father Jiří Prokop Sr. was a chemist and worked at the Ministry of Industry, his mother Věra Prokopová was an accountant at the airport. At the age of ten, he experienced the occupation of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact troops in August 1968, when he was with his grandmother and relatives in a cottage in Krušné hory. Jiří Prokop’s father had been a member of the Communist Party since the 1950s for career reasons. With the onset of normalisation, however, he was expelled from the party and this later had an impact on Jiří Prokop’s life. He was not admitted to high school, so he started working at the Mechanika Praha cooperative, and while working he became an electrician and later completed his high school diploma. In 1978 he got married and had a daughter. A few years later, in 1983, he also started university, but the combination of work, study and caring for his family was demanding, so he did not finish his studies at university. From the late 1970s onwards he was active in the dissident and underground environment. In 1988 he travelled to the West to visit a friend in Munich who had emigrated there earlier. The return to Czechoslovakia was accompanied by problems with border clearance, as Jiří Prokop was carrying not only various electrical appliances and sports equipment, but also literature not commonly available in Czechoslovakia, which had been supplied by Munich emigrants. In June 1989, he signed the petition Several Sentences. During the Velvet Revolution he attended protest demonstrations and participated in the first half of the 17 November demonstration. Jiří Prokop entered the 1990s with enthusiasm and hope, which he placed in the restored democratic regime. He set up his own family-owned electrical installation business, in which he is still active today (2024). From his life experience, he continues to strive to promote democracy in the Czech Republic.