I lived in mutual antagonism with the Bolshevik for years

Download image

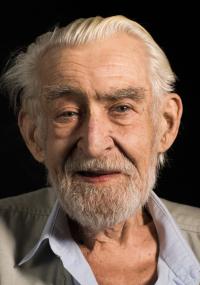

Ilja Racek was born on 24 June 1930 in Prague. After graduating from conservatoire in 1950 he found employment at the Moravian Theatre in Olomouc. He was interrogated and monitored by State Security because of being in touch with a friend who tried to emigrate. Because he was open in his opposition to the Communist regime, he was assigned to the Auxiliary Engineering Corps in Banská Bystrice for his mandatory military service. From 1960 he played at E. F. Burian Theatre and then at Vinohrady Theatre in Prague. He was the only member of the theatre company who refused to sign the “Anti-Charter”, the document signed by numerous prominent Czech artists as a statement of protest against the dissident Charter 77.