The feeling of injustice is terrible

Download image

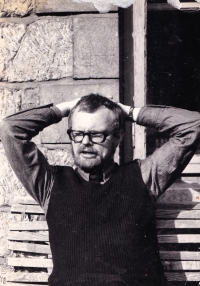

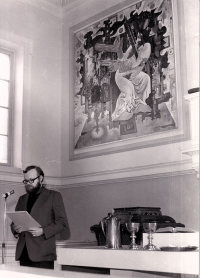

Pavel Rejchrt was born on 20 April 1942 in Litomyšl to Ludvík and Eliška Rejchrt. His father was a minister of the Unity of Czech Brethren and his three sons Luděk, Pavel and the youngest Miloš were also brought up in the faith. From his childhood, he showed great artistic talent. His dream was to study at the Academy of Fine Arts, for which he carefully prepared himself. Although he successfully passed the entrance examination, he was denied admission by a special decision of the rector’s office. He trained as a typesetter and then began his studies at the Comenius Evangelical Divinity Faculty. His love for artistic creation did not leave him, however, and in 1966 he was accepted as a candidate of the Union of Czechoslovak Artists. After graduating in theology, he worked briefly as an occasional preacher of the Evangelical Church of Czech Brethren. In the early 1970s he became a member of a team of mural restorers. His work as a restorer also gave him ample space for his own work, painting, graphic art, writing poetry and lyrical prose, most of which was published after the Velvet Revolution. In 1990, Pavel Rejchrt founded the Christian magazine Souvislosti. In 2024, the witness and his wife lived alternately in Horní Měcholupy and Velichovka.