Eleven days separated them from freedom

Download image

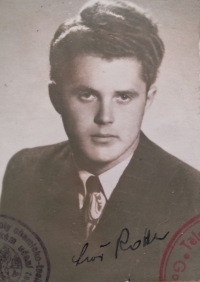

Leo Rotter was born on 7 May 1931 in Brno. His father, Kurt Rotter, came from a Jewish family and was employed as a company director of the Stiassni Brothers factory. His mother Štěpánka, née Weber, had Catholic, Czech-German parents. In 1939, the family attempted to emigrate to England, but the departure was thwarted by the outbreak of World War II. Her father first lost his job and in April 1942 left on one of the transports to Terezín. He went through the camps at Auschwitz and Dachau and died in a German underground factory near Litoměřice in January 1945. His son Leo, a Czech-Jewish half-breed, was hiding with friends in Vysočina towards the end of the war. He and his mother survived the harsh liberation of Brno by the Red Army. After the war, Leo graduated from high school and the University of Chemical Technology, majoring in metallurgy. He connected his professional life with Šmeral’s plants, where he worked his way up to the position of head of the metallurgy department and became an expert in foundry moulding materials. There he also put his knowledge of German to good use, especially after the GDR partnership began. He married and had one daughter. After 1989 he worked as a foreign trade officer at the Feramo foundry. He retired in 2009 at the age of 87. In 2023 he lived in Brno.