Kramatorsk is my place of strength

Download image

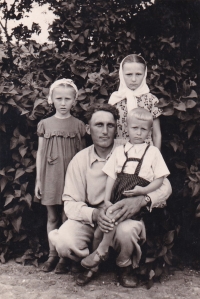

Olena Rudenko is an accountant from Kramatorsk. She was born on December 20, 1976, in Kramatorsk, Donetsk region, into a family where several generations had worked at the Starokramatorsk Machine-Building Plant. While her parents were away working in northern Russia, she was raised under the care of her grandmother, who passed on her knowledge of family history and Ukrainian religious traditions. In 1999, she earned a degree in economics at the Kramatorsk Economic and Humanitarian Institute. She worked as an accountant at enterprises in Kramatorsk and Donetsk. In 2009, she was laid off due to the economic crisis. After that, she traveled seasonally to Crimea for work and observed how life on the peninsula changed after the Russian annexation. At the start of the full-scale invasion, she remained in Kramatorsk until April 6, 2022. On the eve of the missile strike on the city’s railway station, she evacuated together with her daughter. While temporarily settled in Kyiv, she sewed clothing for wounded soldiers following patterns provided by the volunteers of the Sewing Unit. In 2023, she returned to the frontline city of Kramatorsk. Today, she works as part of the team at the Vsi Poruch charity fund, dedicating herself to helping others.