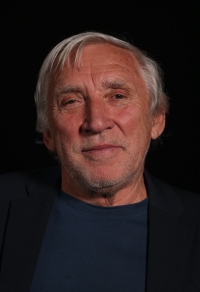

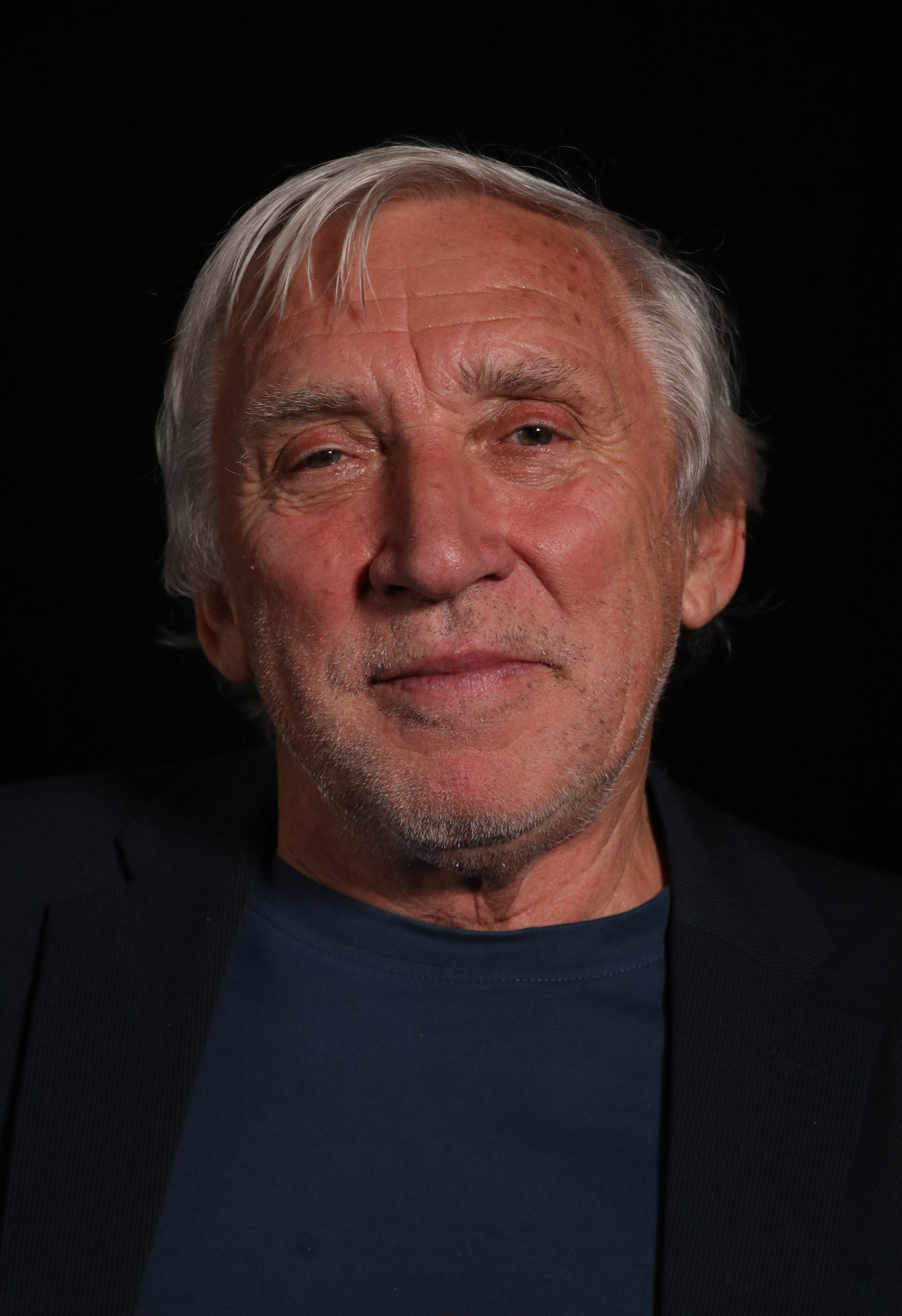

I respect people who are non-conformist and going somewhere

Download image

Born on 12 May 1948 in a middle-class family in Prague, he grew up in Vršovice and later in Vinohrady. From his youth he played sports, in pole vaulting he became Czechoslovakian champion several times in different age categories. At the age of 15 he entered an apprenticeship in Pardubice and trained as a mechanic of measuring and control technology. From 1966 he worked in the Mitas company, while at the same time he completed his studies at the Wilhelm Pieck Secondary General Education School (SVVŠ) in the evening, where he graduated in 1969. The Prague Spring and the subsequent Soviet occupation were defining events for him, and in August 1968, among other things, he took remarkable photographs in the streets of Prague. In 1969-1974 he studied PE and Czech at the Faculty of Physical Education and Sport of Charles University (FTVS UK). He completed his military service as a top athlete in Red Star Prague. After returning from the army in 1975, he started teaching at a school for children with visual impairments in Krč and spent three years there, during which he took his charges on trips and organised a ski course for them. He describes the environment there as a kind of “bubble”, where the atmosphere was not one of normalization. With his 18-year-old son Jakub, he got away through the proverbial alley in the arcade to Mikulandská Street, and fortunately both escaped unharmed. In the following days, there were strikes at the GJK and students and teachers also went on demonstrations on Wenceslas Square. In the spring of 1990, Jiří Růžička was persuaded to apply for a new headmaster of the Gymnasium and succeeded. He led the school through a period of change: everything from the teaching staff to the curriculum and teaching methods to the school building was reconstructed. From the beginning, he emphasized, among other things, experiential pedagogy and sports and physical activities as methods of developing the student’s personality. He co-founded the Association of Secondary School Principals and is the chairman of the board of the Path to Education Foundation. In 2014-2022 he was a member of the Prague 6 City Council. He has also been a senator since 2016, and served as 1st Vice President of the Senate from 2018-2022. He has undertaken numerous adventure expeditions to Alaska, Canada and Nepal. In 2023 he lived in Prague.