A kulak child who signed Charter 77

Download image

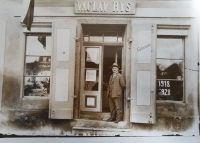

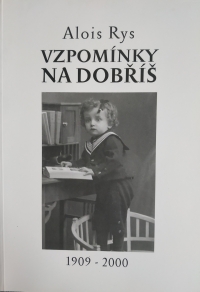

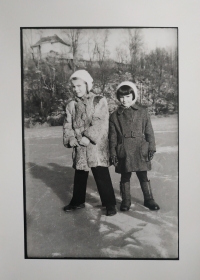

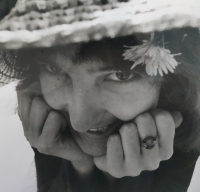

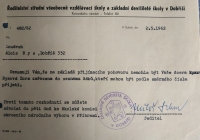

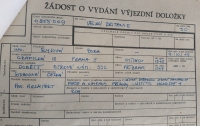

Zora Rysová was born on 9 October 1947 in Prague, but grew up in Dobříš with her parents and two older sisters, Milena and Hana. Her family belonged among wealthier ones, her father Alois Rys was the director of a civil savings bank, her mother Marie Rysová, née Švagrová, was a housewife. However, the Rys family, who held anti-communist attitudes, had their property confiscated after the communist coup in 1948 and their father was deprived of his directorship. Zora Rysová, as the daughter of a kulak and class-unsuitable family, was not given a reference to study at secondary school. In the end, however, she was admitted to study - unlike her two older sisters. She graduated in 1965 and in the same year began her studies at the Faculty of Civil Engineering of the Czech Technical University in Prague. During her university studies, she participated in several demonstrations against the communist regime and was arrested by the police during one of them in 1966. In the summer of 1968, she travelled to England for a temporary job, where she was caught by the news of the occupation of Czechoslovakia while returning home on 21 August 1968. She decided not to return and to stay in England. In 1969, she came back to Czechoslovakia because of her family situation, but she never managed to get to England. She was not able to travel abroad until 1986. Her older sister Milena remained in England, where she married a British citizen, and lived there until her death. In 1972 Zora Rysová finished her studies at the Czech Technical University and in January 1973 she joined the Prague office for monument preservation. During the years of normalisation she made a living restoring sculptures all over the country. She was always close to alternative culture. She used to go to bigbeat concerts and thus got into the environment of underground and dissent. She was also very close to the Catholic circles, especially thanks to the priest Zdeněk Bonaventura Bouše. In 1977 she became a signatory of Charter 77. She was followed by State Security (StB), and repeatedly persuaded to cooperate, which she always refused. In the 1980s, she tried to save the Dobříš Jewish cemetery. She participated in flat seminars, banned concerts and demonstrations during Palach Week in 1989. After November 1989, she became involved in the Velvet Revolution. After 1991, at least some of the property confiscated by the communists was returned to the family. Until her retirement she worked in the field of monument preservation. She remained unmarried and childless. At the time of recording in 2022, she lived in Dobříš.