The next generations have been more or less unteachable since time immemorial

Download image

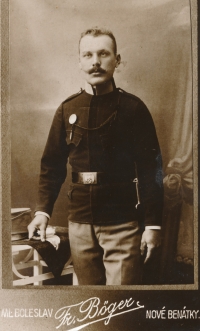

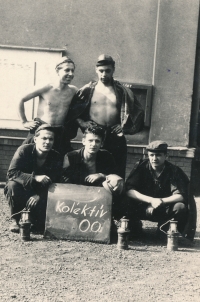

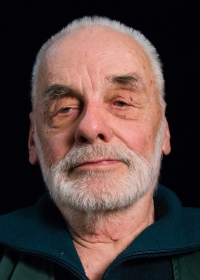

Emil Rýva was born on 19 December 1933 in Prague. He was orphaned shortly afterward and raised by his grandfather and aunt. As the sole heir to a large estate in Štolmíř, he was deprived of his property rights after 1948 and later expelled from the gymnasium. He worked in the national enterprise State Farm in Štolmíř and completed his military service in the Auxiliary Technical Battalions for forced labor in the Ostrava mines. Between 1961 and 1962, he served in the carpentry crew on the youth construction site at the company Kaučuk Kralupy. In 1962, he married and moved to Prague, where he worked as a stoker in the Kinsky Palace and later in the installation crew of the Czechoslovak Association of Visual Artists. From 1970, he worked as a stoker at the national Farm of laboratory animals in Lysolaje. And together with his wife, he raised a daughter. After 1989, he restituted his property, but in a devastated state. Even so, there were people around him who were able to envy him.