Shoot-outs, feuds, and uranium mines. Those were the times

Download image

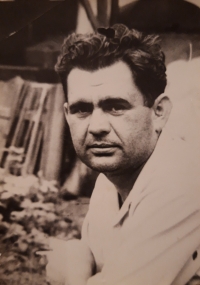

Jaroslav Ryvol was born on 29 September 1930 in Březno in the Litoměřice District. He was one of seven children. His father Otomar worked as a mail carrier and his mother Klotylda was a homemaker. In 1936, the family moved to Děčín, from where they were forced to move during the Munich Crisis of 1938 away from the borderlands toward the interior. His father enlisted in the general mobilization. After his return and a series of moving house, the family settled in Prague, where they lived through the years of the Second World War. In 1924, his mother Klotylda suddenly died of pneumonia. The witness recalls the dramatic days of the May uprising of 1945 as well as the subsequent arrival of President Beneš to the liberated country. After the war, his father moved for work to Liberec, where Jaroslav Ryvol witnessed the expulsion of the Sudeten Germans. He trained as a carpenter and at the end the 1940s he worked in a Prague dockyard. In 1951, he signed up for the Border Guard in Aš. In the mid-1950s, he moved to Nejdek in the Karlovy Vary Region and took on a job as a miner in the uranium mines around Jáchymov. Beginning in the end of the 1950s, he worked for the Pozemní Stavby state company in Karlovy Vary. At the time of shooting the interview (2020), Jaroslav Ryvol was living in Nejdek.