We’re ready to forgive the Czechs for the expulsion, but forgetting it would be rewriting history

Download image

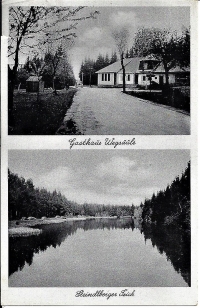

Josef (Sepp) Sager was born on 8 February 1932 in Vimperk (Winterberg in German), raised by his grandparents in the Vimperk suburb of Josefův Důl (Josefsthal) in the valley of the Volyňka river. His mother meanwhile worked as a cook for a Jewish family in Prague. In September 1938 he started his compulsory primary school education, welcoming the arrival of the German Army after the annexation of Sudety into the German Reich. His mother then returned to Vimperk and married Anton Sager, who then adopted Sepp. His stepfather served in the Wehrmacht, returning from the Soviet campaign as a war invalid. In 1942, despite significant opposition from his father, Sepp enthusiastically joined the Hitlerjugend. In April 1945, as a thirteen-year-old, he trained with an anti-aircraft battery firing at a Soviet fighter plane and taking part in street-fighting sabotage against the US Army. He also saw the arrival of Czech Resistance members in Vimperk and viewed mutilated corpses at the local morgue. After the war he took part in a failed German attempt to smuggle property across the Iron Curtain into Bavaria, was imprisoned for five days in a cellar by Czech soldiers and also made to carry out community service in Vimperk as a minor. After staying at the Vimperk collective camp, in August 1946 he and his family were deported to Bavaria. The harrowing journey lasted nine days. In the end they were lodged in a farmhouse cellar in the border town of Grafenau, Josef training as a baker at nearby Schönberg. Soon after, he completed his education and found employment at the local revenue agency, with his many sports accomplishments helping him integrate into German society. Mr Sager has a critical view of his ideological positions during the war, which is why he talks about them openly today. He regularly visits his birth-town of Vimperk and after 1989 he made a number of friends there.