“At home, we received a very strong jewish consciousness, but a weaker religious consciousness.”

Download image

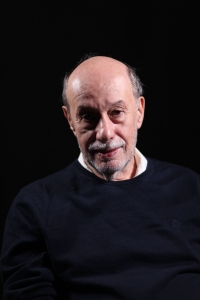

Peter Salner, currently a well-known historian, scientist and ethnographer, known not only for his rich work, but also for his markedly strong relationship with the Jewish community, was born on March 1, 1951 in Bratislava, into a jewish family. The memorial is the second child in a family, because he has an older brother Juraj. Both of his parents survived a labor camp in Sereď. His father, who was officially called Vojtech Salner, was also known as Karol, Martin, Móric or Jozef and even had two dates of birth. The date accepted by the authorities was February 27, 1894, but according to Peter’s mother or other family members, he was born on August 31, 1893. He came from a peasant Jewish family that was engaged by woodcutter. Peter’s mother Alica, who was called Marburgová before the wedding, was born on August 13, 1913 in Rimazavie, North Moravia, and belonged to a Jewish family from a better society. Because of the many differences between his parents, Peter believes that without their chance meeting in Sereď, he would never have been born. Peter as a child, lived on Palackého street, in the center of Bratislava. He attended an elementary school near the house, and was an excellent student with a good memory. Then he continued at the Secondary General Education School, at Vazovova street number thirty-eight. At first he had a dream of becoming a vet, but he became interested in archeology, so in 1969 he decided to send an application to this department. They didn’t open it, but he got advice from his mother that the ethnography was something like that, so he signed up there. He successfully graduated from the Faculty of Arts at Comenius University in 1974. After college, working as an ethnographer, Peter didn’t have it easy. At first he had information that they were looking for someone at the People’s Nutrition Research Institute, but it was just a mistake as they were looking for a stenographer. Subsequently, he obtained the position of a storekeeper in the Municipal House of Culture and Enlightenment. Shortly afterwards, in 1975, he heard from his tutor that they were auditioning for “contemporary research” at the Ethnographic Institute. Despite his poor staff profile, he was accepted and still works at the academy. In the 1990s, he was invited by Martin Bútora to take part in a project about Holocaust survivors. He recorded more than a hundred interviews and became one of the first who started to do something like this in Slovakia. Peter is also a member of the Jewish religious community in Bratislava, and in 1996 he became the chairman of the Jewish religious community for the first time, he held a position until 2013. He became a builder because he transformed the community into a well-functioning community center. In 1970, he met his future wife, Eva, with whom he married in 1974, at the office. The originally planned jewish ilegal wedding, but in the end did not take place. Similarly, Eva comes from a jewish family. Their family became complete on June 2, 1977, when their son Andrej was born.