Communism took almost everything away from us

Download image

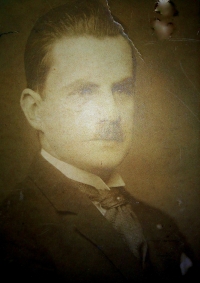

Marta Sandtnerová was born on the 6th of March 1929 in Prague. She is the granddaughter of Stanislav Sucharda, one of the most prominent Czech sculptors and the author of František Palacký’s memorial in Prague, among others. She spent her whole life in an Art Nouveau villa, which was built by her grandfather according to the design of one of the founders of modern Czech architecture, Jan Kotěra, in the Prague quarter of Bubeneč. Marta’s parents were Julius Sandtner, a lawyer and a minister’s assistant at the Ministry of Social Care, and Marta Sandtnerová, the daughter of Stanislav Sucharda, who like her father studied sculpting. Great general artistic talent was also discovered in their firstborn daughter Marta from a very young age. During the war she studied at a grammar school, but immediately after the liberation she started attending a music school in Prague, where she graduated from classical singing. During her childhood and adolescence she became witness to several major changes in the quarter of Bubeneč, which were closely tied to the major events of modern Czechoslovak history. Those who considered themselves the elite at the time always sought to live in the grandiose villas of one of the most prestigious quarters in Prague. Marta remembers the original, mostly Jewish inhabitants of the Bubeneč villas, their escape to foreign countries from the coming of the Nazis, or being sent to the concentration camps, from which none of them ever came back. She remembers how then the Nazi higher-ups in the Protectorate would move into the villas, how they were replaced by Red Army soldiers at the end of the war, and after February 1948 by the chosen from among the ranks of the Communists. She even remembers the Prague Uprising, the coming of the Red Army, and also the post-war events, like the bloody revenge of the Czechs for the occupation, or the kidnappings of “white” Russian emigrants by agents of the Soviet secret service Směrš. Her memories also concern the changes of the Communists’ seizure of power and the following years, including the occupation of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact armies in August 1968. Marta began her artistic career in the year 1954 in the operatic choir of the National Theater, which she only for her pension after twenty-eight years. Sucharda’s villa, thanks to its lower living area, barely escaped nationalization and was left in its original state as the family’s property. In the year 2008 she founded the Foundation of the Museum of Stanislav Sucharda together with her brother Jan, at the initiative of his wife Blanka. Its goal was to care for the works and artistic heritage of their grandfather and his descendants.