Teacher at the Czech-German borderline

Download image

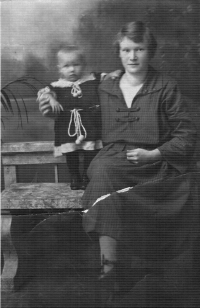

Josefa Šánová, née Pryclová, was born on 25 October, 1922 in Stonařov near Jihlava. Comes from a mixed Czech-German family, which even during WW2 declared Czech nationality. Her mother refused German citizenship. After finishing elementary school and a one-year training, the witness continued studying at the Jihlava teaching institute. When the German occupants closed it in June 1939, she moved to the teaching institute in Moravské Budějovice and after its closure, she finished her studies at the boy´s teaching institute in Brno, where she graduated in June 1941. Later worked as a teacher of German in Jihlava elementary schools. In 1944-1945 she returned to her native Stonařov, where she taught a single class in temporary war conditions. After was German inhabitants were moved from the town and newcomers replaced them, who looked at her suspiciously as German. Especially after the February putsch, her family became a target of bullying on part of communist officials; her husband was thrown out of his job, children were banned from studying and during elections, the family was watched by policemen. Josefa Šánová then left to teach to nearby Pavlov and later Třešt. After many years she returned to Stonařov elementary school.