Our family’s Odyssey was cruel

Download image

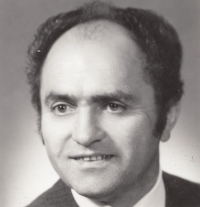

Josef Šára was born on 24 April 1935 outside of Spálené Poříčí in Struhaře in the Plzeň Region to a family of farmers. One of his uncles was Václav Šára, brigade general and commander of the resistance organization Obrana národa (National Guard), executed by the Nazis on 1 October 1941. Josef was still only a little boy when he watched from a hill in Struhaře Plzeň being bombed and the attacks of the low-flying bombers. He remembers the May Uprising in 1945 and being liberated by the American and Soviet armies. After the Communist Party came to power the inhabitants of his village were divided into proletarians and kulaks. After some difficulties he was accepted into a one year agricultural school in Stod in 1950, his second year of school was completed at the Technical School of Agriculture in Klatovy. After graduation, he became a trainee at a center in Nezvěstice, later he continued in Chocenice. As time went on his father’s farmstead was collectivized into the United Agricultural Union (JZD). On 1 November 1957 he began working at a collective farm in Dobronice and later in Chrančovice. From 1 July 1960 he was employed as the main zoo-technician on a farm in Úněšov. His career, which had enjoyed such a promising start, had a turnaround when one day in 1960 he was offered membership in the communist party at the same time they were imprisoning his father for nine months for his apparent disruption of the collective farm in Struhaře. Ultimately, the witness accepted the offer to join the party in fear of what it could mean for his family. Thanks to this he succeeded in obtaining a recommendation to study university, from which he graduated with the highest honors in 1964. As the then main engineer on the farmstead he expressed his disagreement with the occupation of the Warsaw Pact armies during screenings, but managed still to keep his function. As a concession to the then powers that be he graduated from a night-school study program on Marxism-Leninism (VUML) in Plzeň. As a man of agriculture and a farmer, he had contradictory feelings about the fall of the communist regime in 1989. He had to leave the farmstead in Úněšov, which, thanks to his efforts most of all, had turned into an enormous agricultural complex. He returned to his hometown in Struhaře, where he built up a small family farm from the previously desolate farmstead.